Bomber Gap

It was the 1950s. The Cold War was heating up (heh), and the US national security apparatus was consumed by the Bomber Gap, the belief that the Soviets had gained considerable advantages over the Americans through their investments in jet-powered strategic bombers. The earliest warnings date back to 1948 when, fearing a gap, proponents called for increased bomber production in the US. Aviation Week later published an article about a Soviet bomber — the Myasishchev M-4 Bison — capable of carrying nuclear weapons all the way to the US. This sparked intense public debate.

M-4 Bison

Adding fuel to fire was the 1955 Soviet Aviation Day demonstration at Tushino Airfield in Moscow. Ten Tu-95 Bear and M-4 Bison bombersflew past the audience and disappeared from sight, turned around and returned. This was done six times, giving the audience the impression that the Soviets had flown sixty strategic bombers at an air show. Extrapolating from this number, analysts came up with a bleak assessment of US capabilities when compared to the Soviets.

Tu-95 Bear

This estimate was received with some scepticism, notably from Dwight Eisenhower, but he had no data to disprove it.

President Dwight David Eisenhower took heavy flak for downplaying all three, believing these threats to be inflated and not as important as trying to hold the line against budget deficits. Ike’s public reaction to Sputnik, just six weeks after the Kremlin launched the world’s first ICBM, was purposely low key. The Soviets merely “put one small ball in the air” which did not raise his apprehensions “one iota.” Ike’s popularity plummeted.

—Arms Control Wonk

His political opponents seized on the opportunity and held congressional hearings into the matter, concluding that the Soviets had more “B-52 class” bombers than the USAF. General Curtis LeMay testified at these hearings:

The only thing I can say is that from 1958 on, he [the USSR] is stronger than we are, and it naturally follows that if he is stronger, he may feel that he should attack.

The Aircraft

It was against this backdrop that Eisenhower, towards the end of 1954, ordered the development of a long-range high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft. Lockheed developed and delivered the aircraft within eight months. It was capable of flying at an altitude of 73,000 feet, had a range of more than 11,000 km, and an endurance of 12 hours. In order to achieve all this, the aircraft was built to be extremely light, with many parts of the plane bolted together (the tail assembly was attached to the main body by just three tension bolts, for example). The cockpit was cramped and pilots worried that in case of an ejection their legs would be sheared off at the knees. It was called the U-2, and was pressed into action for strategic reconnaissance.

U-2

They were flown mostly by experienced USAF reserve pilots who would resign and join the U-2 programme, run by the CIA, as civilians. Eisenhower had initially asked for the planes to be flown by pilots who weren’t American citizens — for plausible deniability — but the CIA weren’t able to recruit enough candidates on time.

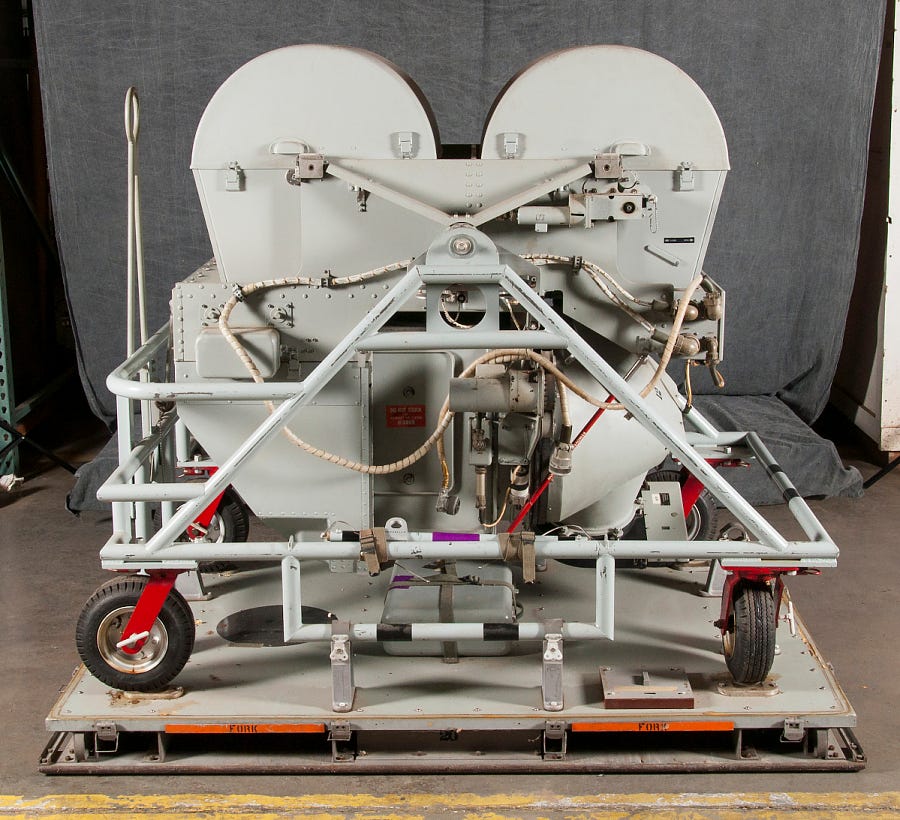

The U-2 relied on the A-1 camera system for reconnaissance. This consisted of two K-38 framing cameras, and one Perkin-Elmer tracking camera. One K-38 was mounted vertically and captured a 17.8 degree swath on 9.5-inch film, while the other captured 36.5 degrees left oblique and right oblique on a separate roll of 9.5-inch film. The Perkin-Elmer tracking camera was mounted on a rocking mechanism that enabled it to take continuous horizon-to-horizon photographs of terrain passing beneath the airplane on 2.75-inch film. The A-1 was later replaced by the A-2 camera system, which had 3 K-38 cameras and one tracking camera, and the B camera system which captured a 200 km wide swath of land for over 3,500 km of flight on 4,000 photographs. Features as small as 2.5 feet could be resolved from a height of 65,000 feet.

B camera system

The CIA was convinced, based on studies of old Soviet radar systems, that the Soviets could not track U-2 aircraft flying at high altitude. And even if they were tracked, shooting down a plane flying at 70,000 feet was beyond any fighter aircraft the Soviets had in inventory. The MiG-21, which had its first flight in 1955 and was inducted in 1959, had a service ceiling of 57,000 feet and initially had poor endurance.

1 May 1960

It was a Sunday when Gary Powers took off in a U-2 from Peshawar in Pakistan and flew in a Northwest heading, flying over Afghanistan before entering USSR airspace. Just three weeks earlier another U-2 piloted by Bob Ericson had crossed into Soviet airspace over the Pamir mountains in what is now Tajikistan. His plane had been detected and numerous attempts were made by MiG-19s and Su-9 aircraft to intercept it. After photographing four sensitive locations including the Dolon airbase, a Tu-95 facility in present-day Kazakhstan, Bob had landed his plane in Zahedan, Iran.

The next U-2 flight was scheduled to take off from Peshawar on 28 April, and the aircraft — Article 358 — had been ferried from Incirlik Air Base, Turkey, to Peshawar. A C-130 carried the ground crew as well as pilot Gary Powers and his backup, Bob Ericson. Bad weather over the Soviet Union delayed the U-2 mission by a day, so Bob flew Article 358 back to Incirlik, while another pilot ferried a different U-2, Article 360, from Incirlik to Peshawar. The weather cleared on 1 May, and Gary Powers took off. He planned to photograph ICBM sites at the Baikonur Cosmodrome and Plesetsk Cosmodrome before landing in Norway. A plutonium processing plant at Mayak in Russia was also on his itinerary. His flight path crossed 2,900 miles of Soviet airspace.

Powers flew over Baikonur Cosmodrone and photographed the ICBM sites before heading north for the location of the Mayak plant. Unfortunately for him, the Soviets were expecting the flight and all air defence assets had been placed on alert. As soon as the U-2 was spotted on radar, Lieutenant General Yevgeniy Savitskiy of the Soviet Air Force ordered all available units to:

attack the violator by all alert flights located in the area of foreign plane's course, and to ram if necessary.

Multiple MiG-19s were scrambled but failed to intercept the U-2 due to the extreme altitude at which it was flying. The CIA was confident that the U-2 could not be intercepted by Soviet aircraft. A U-2 flight on 5 July 1956 had overflown Moscow and Leningrad searching for M-4 Bisons. When photographs were processed they showed tiny MiG-15s and MiG-17s scrambling and failing to intercept the U-2. This became something of a regular feature and the MiGs would, by virtue of trying to intercept the U-2, oftentimes interfere with photographs.

Powers was taking notes, flying at 70,500 feet and four hours into his mission, when a bright orange flash to the right and behind his aircraft surprised him.

I looked up, looked out, and just everything was orange, everywhere. I don't know whether it was the reflection in the canopy [of the aircraft] itself or just the whole sky. And I can remember saying to myself, 'By God, I've had it now.'

—Francis Gary Powers

His aircraft had been targeted by the S-75 Dvina Surface to Air Missile. His U-2 was not its first victim, though. The missile had been inducted in 1957, and had claimed a Taiwanese Martin RB-57D Canberra high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft near Beijing in October 1959. But that kill had been publicly attributed to intercepting aircraft in order to keep the capabilities of the S-75 secret.

S-75 Dvina

The shockwave sheared off the tail and a wing and the aircraft began spiralling down towards the ground. At first Powers thought of ejecting, but was worried that the action would cause his legs to be sheared off in the cramped cockpit. He needed to get himself in the perfect position before ejecting. But then he remembered an alternative: open the canopy and climb out.

When he released the canopy, he was sucked out of the aircraft but remained tethered via his oxygen line. After a bit of wrestling with it, the line snapped and he floated clear of the aircraft. In all this he had been unable to activate the self-destruct mechanism on the aircraft’s dashboard which would have destroyed the camera system.

After his parachute deployed, and as he floated down, he saw a car tracking him. Soon after he landed, and moments after he had destroyed the maps detailing his mission parameters, he was apprehended and taken to KGB headquarters.

A total of 14 S-75s were launched that day at the U-2. One of them downed a MiG-19 that was flying an intercept course to the U-2. The pilot — Sergei Safronov — ejected successfully but died of injuries sustained from the event.

Flight path

Aftermath

The Soviets announced that a US aircraft had crashed in the Soviet Union, but by keeping the announcement light on details they let everyone assume that the pilot was dead and the aircraft was destroyed. At that moment Powers was being interrogated in Lubyanka prison by the KGB. The interrogation continued for 19 harrowing days. He initially attempted to limit the information divulged during the interrogation, but the KGB gleaned a fair bit from reports appearing in the western press. He did, however, repeatedly lie to the KGB about the maximum altitude of the U-2, telling them that it was 68,000 feet, considerably lower than its actual flight ceiling.

Lubyanka, Moscow

Eisenhower was assured by the CIA that the aircraft was destroyed in the crash and the pilot was dead. Another U-2 was quickly painted in NASA colours, and a cover story was released claiming that an aircraft on a routine weather mission had gone down after the pilot’s oxygen system malfunctioned.

The Soviets had recovered the camera system and therefore knew for certain that the cover story was bunk. The interrogation, in turn, corroborated everything. Khrushchev waited, letting the Americans completely commit to their cover story, then announced triumphantly that the pilot had been captured alive. He also displayed the wreckage of the aircraft. Powers was put on public trial on 17 August. He confessed and spoke of his shame and regret. At the end of the three-day trial he was found guilty of espionage, and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

He served the better part of two years. On 10 February 1962, Captain Francis Gary Powers, USAF, was repatriated to the United States in exchange for KGB Colonel Rudolf Abel (whose story has been covered in another post on Espionage&) at Glienicke Bridge in Germany.

Back Home

Upon his return the the US, Powers found that while he was in a Soviet prison editorials written back home had accused him of being a defector. Some claimed that he had landed the plane intact and spilled all kinds of secrets. Others pointedly questioned why Powers hadn’t committed suicide despite carrying a poisoned suicide pin hidden inside a silver dollar.

He was invited to speak at a committee hearing in the United States Senate, was exonerated, and given $50,000 in back pay to cover the period of confinement in the USSR.

Wooden model used by Powers to explain what happened to his aircraft

He was debriefed extensively by the CIA and Lockheed Martin, following which the CIA released a report stating that Powers had acted as per instructions given to U-2 pilots. But perhaps all that wasn’t enough to clear his name completely.

He worked at Lockheed as a test pilot from 1962 to 1970, but was fired after his book Operation Overflight reportedly ruffled feathers at the CIA. He became a news helicopter pilot, but his helicopter crashed in 1977 when it ran out of fuel a few miles short of Burbank airport. The crash was attributed to pilot error, but his son claimed that a mechanic had repaired a faulty fuel gauge without informing Powers. Apparently, when the gauge showed ‘Empty’, the helicopter still had enough fuel to fly for 30 minutes. Since Powers wasn’t informed of the repaired gauge, he misread how much fuel he had.

He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 2000, and the Silver Star in 2012.

Sources

BBC, CIA, Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum.

Shaunak Agarkhedkar writes spy novels. His first two - Let Bhutto Eat Grass & Let Bhutto Eat Grass: Part 2 - deal with nuclear weapons espionage in 1970s India, Pakistan, and Europe.

Who'd have the awareness to push the self destruct button while hanging off of the oxygen line from a plane at around 70k ft!!