A fake bank, Colombian cartels, and money laundering

Or "What is the Black Market Peso Exchange and how do billions of dollars reach Colombia?", and "Where did that f%#*&@$ bank go?"

Too much cash

In the 1990s, drug sales in the United States were generating more than $50 billion a year in revenue for Colombian cartels in cash transactions. But as long as all that cash remained in the United States, it was effectively useless for the cartel bosses. They needed to repatriate it to Colombia. For reasons.

There was one major problem: logistics.

$50 billion in $10 bills would weigh approximately 5,000 tons, occupy around 199,357 cubic feet, and require about 1,246 pallets stacked 10 feet high for practical storage and transportation.

Since a C-130J Super Hercules can fly 8 pallets / 19.95 tons, it would take more than 250 flights to deliver all the cash. In other words, a fully loaded C-130J Super Hercules would have to fly from the United States to Colombia every weekday throughout the year.

This was completely unfeasible for obvious reasons.

Which is not to say that no dollars were flown back. At one point, aircraft flying Pablo Escobar’s cocaine into the United States were flying dollars back to Colombia. And Escobar’s Medellín Cartel was spending $2,500 per month on rubber bands for bundling the dollar bills.

But most of the cash had to be deposited in American banks. In money laundering, this is called Placement. And since federal regulations require banks to report cash deposits greater than $10,000, the money had to be split into multiple deposits below that threshold.

The scale of the cartels’ cash problem becomes apparent when you consider that placing $50 billion in this manner requires more than 5 million transactions. The cartels had neither the expertise nor the manpower to do this themselves. More importantly, the cartels found it tedious as hell.

“It became more of a problem to count the money and stack it. I mean, it took hours upon hours and hours to do it and recount it and go over and over it again. It was tedious as hell. Money became an obstacle. You know, it started to take the fun out of the whole thing, believe it or not.”

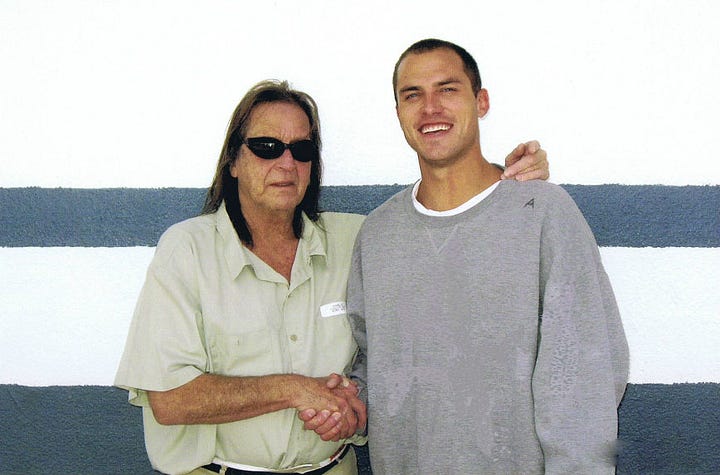

—George Jung, convicted drug trafficker who worked for Carlos Lehder, co-founder of the Medellín Cartel.

So they outsourced it.

Black Market Peso Exchange

After negotiating an exchange rate that was lower than the official rate — usually 40% lower — the cartels would hand the cash over to a money broker in the United States.

“The money could be in boxes, shopping bags, suitcases, a car. Sometimes the money would be in the truck of a car and the traffickers would just give you the keys to the whole car.”

—David, a money broker

The money broker employs a large number of ordinary Americans called runners. Their job is to take the cash and make a large number of deposits in hundreds of different bank accounts controlled by the broker. This forms a minor plot point in Sicario. In case you haven’t seen the movie yet, I cannot recommend it enough. Here’s the bank scene involving a runner.

Each cash deposit transaction has to be significantly less than $10,000, which is the threshold at which the bank is obliged to report it to their regulator. With the deposits completed, the money is now placed in the US banking system.

The broker’s representative in Colombia, meanwhile, negotiates terms with Colombian businessmen who need US Dollars for payments to American companies for goods and services. The broker offers a discount to the official rate, usually 20%.

Once the terms are agreed upon, the broker makes the payment to American companies in US Dollars on behalf of the Colombian businessmen. In turn, the businessmen transfer a negotiated amount of Colombian Pesos to bank accounts controlled by the cartels. Sometimes, these two payments (US Dollars and Colombian Pesos) do not take place concurrently. In such a situation, the broker will pay the cartels from his own bank accounts in Colombia.

In the end, the cartels get their money, and the businessmen get cheap dollars. The broker gets a fat commission and keeps the difference in exchange rates. That is the Black Market Peso Exchange.

Dan the money broker

In the early 1990s, one such money broker approached the US Embassy in Ecuador and offered information about a vulnerability in the drug trafficking business. Eventually, his offer found its way to two agents, Skip Latson with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and Bill Bruton with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). They decided to call him Dan. Based on the information Dan shared, Skip and Bill convinced their bosses and embarked on Operation Dinero.

They began by creating a bank in Anguilla, a British Overseas Territory in the Carribbean. Apart from tourism, offshore banking and offshore incorporation form the bulwark of the island’s economy. So it made sense to form RHM Trust Bank in a location where money laundering was already a significant business.

From the get go, the bank was configured for money laundering and little else. There were no branches, it had no ATMs, and they did their best to dissuade ordinary people from opening accounts.

The bank’s efforts were completely focused on laundering drug money, and Dan helped by sending customers their way. When a drug trafficker needed money laundered, he would send RHM an account number and a beeper (also known as a pager).

The trafficker’s people would reach out to RHM using the beeper, and then Skip’s people (DEA agents) would go pick the cash up from nondescript locations in the United States. That cash would then be deposited into RHM Trust Bank’s account at the local bank. Skip and Bill would then wire that money — less RHM’s commission, which was between 8-9% — to the account number given by the drug trafficker.

When Skip and Bill wanted to know who the real owner of the money was, they would wait for an additional day before wiring the money. That delay was often sufficient for the real owner to give RHM bank a threatening phone call, revealing his identity.

As word spread of the excellent service offered at competitive rates by RHM Trust Bank, more and more drug traffickers began sending it their money laundering business. And the information Skip and Bill began collecting blew their collective minds.

The story concludes in The Copernicus of Cocaine.

The Copernicus of Cocaine

Continued from this post on Espionage&. When Skip Latson and Bill Bruton proposed setting up a fake bank to their superiors, the targets they had in mind were Colombian, with Pablo Escobar at the top of the list. And as soon as it opens, RHM Trust Bank gets its first clients from among the Colombians thanks to introduct…