Balakot and and the problem of Battle Damage Assessment

Limitations of amateur Satellite Imagery Analysis

This article originally appeared in Newslaundry in April 2019.

It draws heavily from many academic and military sources, specifically works by Jan Frelin at the Swedish Defence Research Agency and John T. Rauch of School of Advanced Airpower Studies, Maxwell Air Force Base.

Context

The Balakot airstrike predictably set off a media frenzy. Traditional media houses and participants on social media rushed to assess the damage inflicted on the Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) camp, primarily using satellite imagery. The Pakistan Army (PA) twice called off visits of journalists to the site of the attack citing “security concerns” to deny journalists access, preventing independent corroboration of damage. More than a month after the attack, they finally took eight journalists to the camp in what was obviously a carefully choreographed event. Even then, reports mentioned that some areas of the site were covered with tarpaulin and access to them was denied to the journalists. Some think tanks used commercially available satellite imagery to claim that the airstrike appeared to be a “botched operation”. Retired professionals and journalists pored over satellite imagery themselves and identified spots where the munitions pierced the roofs of the targeted buildings which would be consistent with the type of munitions used. The Indian Air Force (IAF) gave the Government of India (GOI) a dossier containing twelve images of the camp taken using Synthetic Aperture Radar. The IAF contends that the images clearly show entry points on the roofs of the targeted structures consistent with the type of munitions used-reportedly the penetrator variant of the SPICE-2000. Air Chief Marshal B. S. Dhanoa’s factual statement that the IAF doesn’t count casualties but targets ended up adding to the confusion. The approach taken by most journalists and think tanks relies almost entirely on satellite imagery for assessing damage. The author believes such approaches are inadequate and seeks, through this article, to dissipate the misinformation and confusion prevalent in public discourse regarding damage assessment.

Precise Assessment of Effects

Battle Damage Assessment (BDA) is the precise assessment of the effects of stand-off weapons on their targets. It determines the effectiveness of the weapons and informs subsequent planning. BDA is an intelligence activity that works with various kinds of evidence to determine effects on target. Satellite or Aerial Imagery (IMINT), Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) and Human Intelligence (HUMINT) are the primary sources of evidence relied upon for BDA [1].

The US Department of Defence defines BDA as “The timely and accurate estimate of damage resulting from the application of military force, either lethal or non-lethal, against a predetermined objective... Battle damage assessment is primarily an intelligence responsibility with required inputs and coordination from the operators. Battle damage assessment is composed of physical damage assessment, functional damage assessment, and target system assessment.” [2]

The problem of damage assessment was first identified during the First World War when aviators in airplanes and Zepplins dropped the first bombs on targets in August 1914 [3]. As air planners needed feedback of the effectiveness of prior actions in order to plan next steps, they began debriefing air crews and, occasionally, examining photographic evidence. This was the origin of what was known back then as Bomb Damage Assessment.

During the Second World War, BDA primarily relied on aerial imagery analysis with the United States establishing separate units of modified bombers with equipment for photoreconnaissance. Pre-attack and post-attack imagery were analysed comparatively to determine damage to the target. Sometimes weather conditions interfered with the acquisition of post-attack imagery, with targets sometimes obscured for weeks. The way around this was for a part of the bomber fleet to carry cameras to record strikes in progress [4]. However, relying purely on aerial imagery was found to result in inaccurate results.

Inadequate? Inadequate!

The United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) conducted after the Second World War sought to validate BDAs by comparing actual damage on the ground to the damage perceived from aerial imagery [5]. The survey indicated that BDAs were inadequate, with wide variance in the assessment of primary effects of bombing raids. The photo interpreters were even less successful at interpreting secondary effects because of the cardinal rule of reporting only what could be seen by another interpreter [6]. An observation of particular relevance to the Balakot operation is that analysts struggled to assess the effects of bombs that exploded well below the roof [7]. One officer of the USAF explained the problem eloquently when he said, “bodies don’t cause secondary explosions.”

The Precision Munitions Problem

This problem was exacerbated with the arrival of Precision Guided Munitions (PGM) around the time of the Persian Gulf War. A PGM is intended to precisely hit a specific target to minimise collateral damage and increase lethality against intended targets [8]. Hardened PGMs designed to penetrate reinforced concrete before detonating leave only small holes in targets–specifically in the target’s roof–and depending on the warhead, “most of the explosion’s effects are contained within the target” [9]. The United States military sought to get around this problem by using intercepts of communications and signals in conjunction with imagery but were faced with the consequent issue of long delays as the disparate pieces of intelligence were collected, collated, contextualised and analysed to present a considered assessment. But after the war ended, the Gulf War Air Power Survey repeated the conclusions of the USSBS that BDA was inadequate [10].

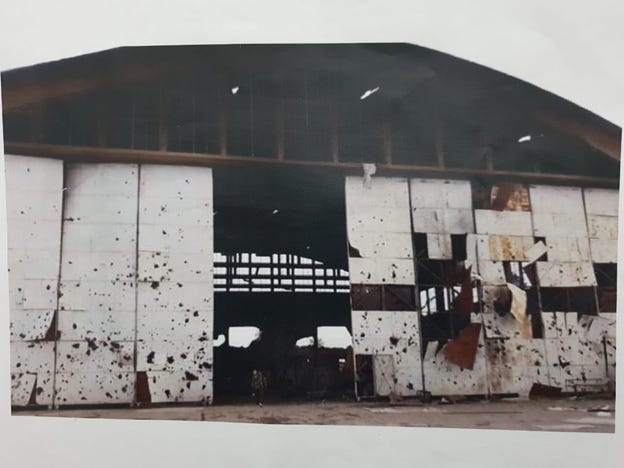

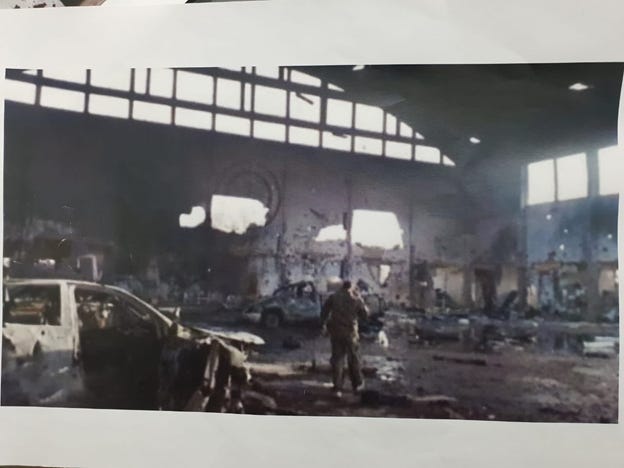

Israeli strikes on a Syrian hangar at Syria’s T-4 military base near Homs in April 2018 serve as a useful illustration of the difficulty of performing accurate BDA using just satellite or aerial imagery or any other imagery taken from outside the structure in case of penetrator-type PGMs.

Figure 1 shows the outside of the hangar. A few panels appear to be blown out, but unlike what a layperson would expect–a completely bombed out structure with walls and roofs blown off–the structure seems relatively intact.

Figure 2 shows absolute destruction within the hangar.

We don’t know details of the type of weapons used by Israel for this strike, or the type of warheads deployed on those weapons. However, PGMs programmed to penetrate a structure before detonation need not destroy the structure significantly. The walls and the roof are intact even though neither appear to be made of reinforced concrete. Seen from the air, the warehouse roof would only show holes made by the PGMs when they penetrated the structure. BDA based on IMINT from above will significantly underestimate the devastation caused by the strike.

Refine! Refine! Refine!

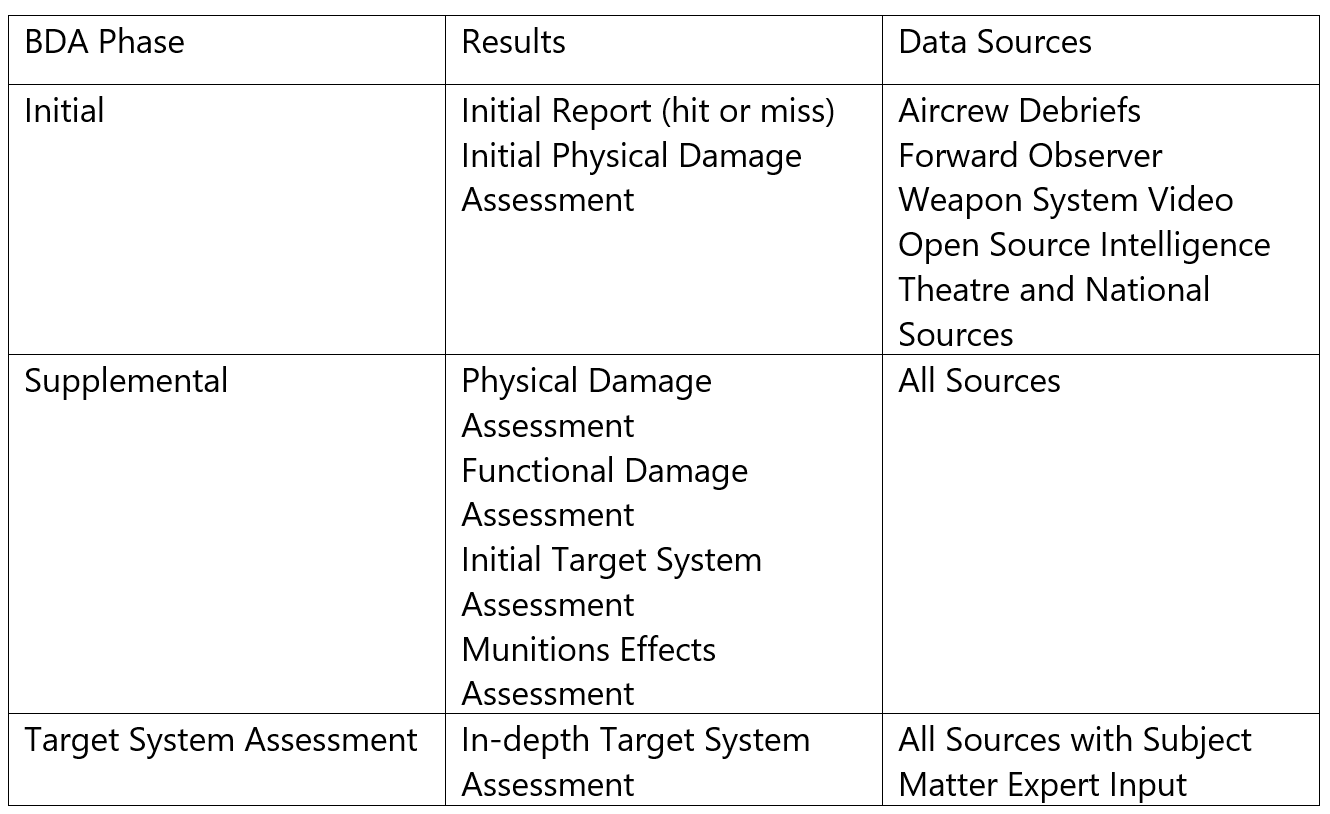

Many committees and working groups were constituted by the intelligence community in the US to address these challenges. The outcome documents define three phases of BDA:

Mapping this framework to Balakot, the IAF would have performed the Initial Assessment, with the National Security apparatus taking over the task of the Supplemental Assessment. A Target System Assessment wouldn’t be relevant. During the Initial Assessment, Aircrew Debriefs and Weapon System Video would confirm that the intended targets were hit.

The Initial Assessment would answer the question: Did the weapons impact the target as planned?

The assessment would include confidence levels, as well as extent of perceived damage. This was the crux of the statement given by the Chief of Air Staff where he pointed out that the IAF did not count casualties.

The types of munitions used and their characteristics would be factored into the Supplemental Assessment which would take the Initial Assessment and layer intelligence inputs from other sources. This would include SIGINT from NTRO which had helped confirm 300 active mobile connections at Jaba Top in the days prior to the attack. Depending upon NTRO’s capabilities, if all or most of those active connections went dead after the attack, that would be a strong indicator. HUMINT from R&AW and IB, and IMINT from our own satellites and from friendly countries would play a crucial role in forming the Supplemental Assessment. It would also incorporate Open Source Intelligence (OSINT): accounts like the one by journalist Francesca Marino whose sources confirmed that the death toll at Jaba Top was between 40 to 50 and included JeM trainers and bomb experts and retired Pakistan Army officers; the February 28 audio clip from the JeM event at Peshawar where the terror group acknowledged the attack on its camp, etc.

The Supplemental Assessment would answer questions like:

Did the weapons achieve the desired results and fulfil the objectives and therefore the purpose of the attack?

How long will it take enemy forces to regain functionality?

Are strikes necessary to inflict additional damage?

Overreliance on IMINT

The government has, through unnamed sources and the Chief of Air Staff, effectively released the Initial Assessment that the bombs struck their targets. It has also shown multiple journalists high-resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar imagery that clearly shows the penetration holes made by the PGMs, proving conclusively that the IAF hit the targets. For various reasons that need no elaboration, efforts have been focused on disproving this. But these efforts appear ignorant of lessons the US Intelligence Community learnt during the Persian Gulf War: Relying on IMINT when seeking to assess the effects of penetrator-type PGMs is an exercise in frustration. Think tanks and journalists are relying completely on IMINT from low-resolution sources and have ignored even the sampling of OSINT mentioned above. Particularly damning is their complete discounting of the fact that for more than a month after the airstrike, the Pakistan Army prevented journalists from accessing the camp at Jaba Top. And even when they did finally take journalists on a choreographed tour, many areas of the camp remained covered in tarpaulin and access to those areas was denied. Amateur analysts are stuck at the Initial Assessment phase and the lack of access to Weapon System Video or Aircrew Debriefs, coupled with their selective reference, if at all, to OSINT takes away from the credibility of their conclusions.

Other References

[1] “Purposeful Assessment: Assessing the Effects of Military Operations”, Jan Frelin, Swedish Defence Research Agency

[2] Joint Publication 1–02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 12 April 2001, 50.

[3] “Assessing Airpower’s Effects: Capabilities and Limitations of Real-Time Battle Damage Assessment”, Lt Col John T. Rauch, School of Advanced Airpower Studies, Maxwell Air Force Base

[4] Ibid

[5] USSBS, European War

[6] Lt Col John T. Rauch

[7] Ibid

[8] “Precision guided munitions and the new era of warfare”, Richard Hamilton

[9] Ibid

[10] GWAPS

Shaunak Agarkhedkar writes spy novels. His first two - Let Bhutto Eat Grass & Let Bhutto Eat Grass: Part 2 - deal with nuclear weapons espionage in 1970s India, Pakistan, and Europe.