How to fool the CIA: Conclusion

The year 2009 saw an audacious attempt to track and kill Ayman al-Zawahiri. This is how it ended.

Continued from How to fool the CIA: Part One.

A tête-à-tête

Eager to get all its ducks in a row before your next meeting with Zawahiri, the CIA leans on their friends in the Mukhabarat. Langley wants one of their own to meet you, to get to know you better, and to convince you to help them track Zawahiri. And they begin exploring possibilities with the Mukhabarat.

The first idea — of flying you back to Amman for a tête-à-tête — is abandoned just as soon as it’s brought up. Regardless of how well it is executed, the CIA flying you out of Pakistan right before Zawahiri’s next appointment will be disastrous for you. And they don’t want you dying before you’ve done their bidding.

Your handler then emails you, mentioning that the Americans are keen to meet you face to face, and want you to travel to Afghanistan. So you invite him and the Americans to meet you in Miranshah, a town nearest to your location, and a place where — you assure your handler — you can ensure privacy for a quiet meeting.

But the handler balks, as does his leadership and the CIA. For starters, Miranshah is home to the leadership of the Haqqani network. This insurgent group was once a CIA client, fighting side by side with Osama bin Laden during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Later, they pledged allegiance to the Taliban. And they’ve held firm to that ever since.

In true CIA-client fashion, the Haqqanis now take pride in fighting and killing American soldiers in Afghanistan.

Jalaluddin Haqqani practically owns Miranshah, and any CIA officer foolish enough to venture there would be lucky to count the rest of his or her life in weeks if not days. Not that your handler won’t make an equally tempting target. As a member of the extended royal family of Jordan, his capture and execution would be a propaganda coup for al-Qaeda or the Haqqanis.

When your handler flatly refuses to consider Miranshah, you propose meeting at Ghulam Khan Kalay, a village located almost on the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. But it’s little more than a few dozen huts, offering almost no place for spies to meet in private. And it’s marginally on the Pakistani side of the Durand Line

Khost

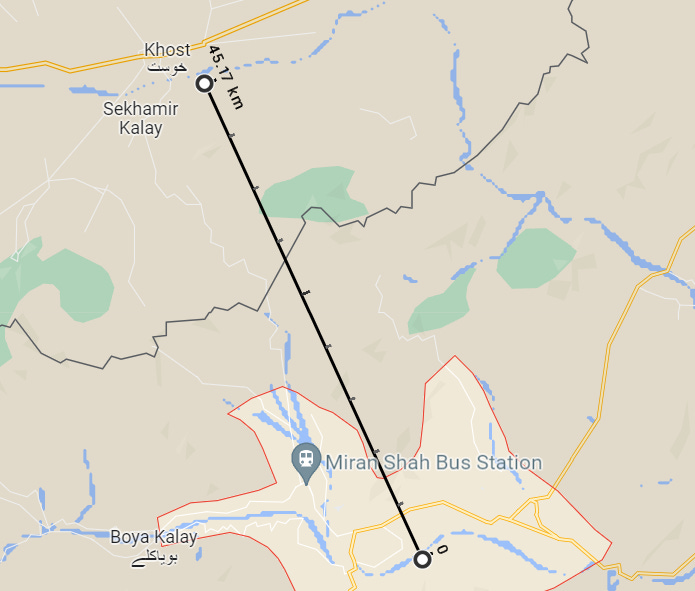

The handler writes back, asking you to make your way to Khost in Afghanistan, barely thirty miles from Miranshah as the Predator flies. There is an American military base there, he tells you. A secure location where they can meet in peace, with American guards ensuring that nobody ventures close enough to see him

The absurdity of the whole thing! You write back declining the invitation, reminding your handler that you are the one taking all the risks. Many objections come to mind, the foremost being that outer security around the base is handled by Afghan soldiers. It isn’t unreasonable to assume at least some of them are sympathetic to al-Qaeda, and might identify you to them as the man who met the CIA.

But the handler pushes you to go to Khost. The Afghan soldiers, he tells you, will be kept away. They will not stop your vehicle at the gate, and will be ordered to turn away. The only people allowed to see you will be Americans. And your handler.

Forward Operating Base Chapman is located at the site of a Soviet airstrip to the east of Khost. Littered with damaged and disabled aircraft, the base is known to every insurgent in the region. Deep within it, however, is a fenced off area manned by the CIA. This is where your handler wants to meet you

You keep declining their invite, but each time your refusal is less forceful, less vehement. They’re grinding you down. And the CIA leadership is consumed by optimism. The mere thought of getting Zawahiri…

The CIA base chief at FOB Chapman has even worked out your logistics, and cooked up a cover story for you. As Zawahiri’s doctor, you need to travel to Miranshah to buy medicines for the old man.

After a lot of bureaucratic wrangling, mostly within the CIA itself, they propose to the Mukhabarat that your handler and his CIA liaison in Amman be present in Khost to debrief you.

But the Mukhabarat…

The Mukhabarat aren’t quite as sanguine. Over long years of dealing with extremists, they’ve learnt that while low-level thugs can be flipped with relative ease, true believers — the ideologues — never really change sides. They may pretend they’ve lost all sympathy for the cause, but deep down, the ideology remains firm. And for that reason, true believers make terrible double agents.

Abu Dujana al-Khorasani, a senior officer from the Mukhabarat tells the CIA, is a true believer.

Another factor weighing against him is his insistence on meeting in Miranshah when a secure location is available just thirty miles away. This insistence strikes the Mukhabarat as suspicious, and the officer warns his CIA counterpart that you might lead them into an ambush.

The CIA counterpart thanks him for his insights, but takes no action. Far too many people in powerful places now know of this operation and have their hopes pinned on it. This is no longer something that can be stopped based on a hunch.

The handler and his CIA liaison

Your handler’s CIA liaison, however, is wary. He writes a memo to your station chief in Amman, warning that the CIA knows very little about you, and therefore they need to be cautious, go slow. The station chief believes this lack of knowledge about you and your motivations is precisely why they need to meet you in person, and takes no action.

Another of the liaison’s concerns is that there are too many people involved: fourteen intelligence officers and a driver. And that’s just the count at FOB Chapman. This strikes him as absurd. Every other meeting he has had with an agent has involved him, his partner, and the agent meeting at a public place or in his car. And for good reason. The less the agent knows about the people involved, the less he can betray to the enemy.

And his third complaint was that they — the CIA — are letting you dictate terms.

But with his own station chief declining to intervene, the liaison quietly accompanies your handler to Khost a few days before Christmas in 2009 and, amidst a feeling of impending doom, prepares for the meeting.

Your handler briefs the base chief about you, warning her that you’re moody and have a fragile ego. They are to treat you with kid gloves. The base chief agrees, and goes about planning for your reception at the base, taking care to address your cultural sensitivities.

‘He has to be made to feel welcomed,’ she tells her subordinates.

This sets her on a collision course with the CIA’s security chief in Khost, who believes that there is a fundamental problem with the way your reception has been planned: too many people standing too close to an agent who has lived undercover and cannot be trusted. But despite his arguments, the base chief has her way. There’s too much pressure from Washington and Langley to allow the meeting to be derailed.

‘You win’

You don’t make contact for many days, letting the handler and his friends stew in anticipation. Then, on December 28, you email your handler.

‘You win,’ you say, agreeing to travel to Khost the next day.

But you take time to build up your nerve, and reach the checkpoint at Ghulam Khan Kalay more than twenty-four hours later than expected, after an exhausting journey from Miranshah carrying a heavy load. Your leg aches from a motorcycle accident a few months earlier. It’s hot, and you’re holding a Jordanian passport with a Pakistani visa that expired months ago.

You get into the line of people waiting to cross into Afghanistan, and inch forward to the border check. Suddenly, you see someone wave to you from the line of taxis waiting for passengers headed to Afghanistan. When you walk towards him, he greets you and opens the door for you.

Now you’re inside a white sedan queued up behind other vehicles, inching towards the border check. At the check post, you build up the courage to show your documents. But the driver flashes his identity card, and the car is waved through.

Once on the Afghan side, the driver makes a quick call from his cell phone and the two of you set off for Khost. On the way, he pulls onto a mud track heading into a village and, after checking for a tail, you change cars.

As the airfield comes into sight, you borrow his cell phone and call your handler, repeating your concern about Taliban spies in the ranks of the Afghan soldiers guarding the perimeter. Then you ask once again if you’ll be treated as a friend. Your handler reassures you on both counts.

FOB Chapman

As the car approaches the base, it snakes its way through barriers designed to funnel traffic into a single lane that is covered by a heavy machine gun. You see the checkpoint but, as your handler promised, you are not stopped or searched. The car passes the checkpoint, makes its way past a few more barriers, and enters FOB Chapman.

After two more checkpoints — each one of which allows the car to pass unmolested — as the gate behind you is closed, you see a building with a dozen-odd people standing in the foyer. The driver parks the car a couple of dozen yards away from the foyer.

You’re looking at your handler in that crowd waiting for you when the car door is opened. A bearded man with a gun reaches for you with his hand, but you slide away from him on the rear seat, open the door on the other side, and exit the car. There’s a grimace on your face from the aching leg.

You notice your handler calling your name. You begin walking towards him, your mind invaded by a million morbid thoughts. The world around you slows down. You hear shouting. The men surrounding you are agitated. They have their guns drawn, pointing at your head.

Terrified, you mutter a prayer. Your right hand is in your pocket now. They’re shouting about it. And yet you continue walking towards them. Suddenly, you’re surrounded, with men on your left and right, guns drawn, blocking you from the rest of the people in the foyer.

With a twitch of your finger, you detonate your suicide vest.

About the attack on FOB Chapman

Humam al-Balawi, the Jordanian double agent, turned out to be a triple agent. The senior man at Jordan’s Mukhabarat had been correct when he assessed that Balawi was an ideologue that hadn’t really turned.

After the death of Baitullah Mehsud, Balawi came to the attention of mid-level al-Qaeda leaders. At first, they tried to provide weapons training to him. But Balawi was atrocious at using a rifle, and completely out of place in a squad of al-Qaeda fighter.

That was when the al-Qaeda operative arranged for the video with Atiyah Abd al-Rahman and, after it had hooked the CIA, arranged for Zawahiri’s medical records to reel them in.

While all this was happening, Balawi fed information to his handler that led to drone strikes on a few al-Qaeda operatives, building his credibility even further with the CIA. A sign of the credibility he enjoyed is the presence of the deputy chief of CIA’s Kabul station at FOB Chapman that day. The deputy chief was to place a call to President Obama directly after the meeting.

The operatives he gave up, however, were all low-level functionaries.

Before he left for Miranshah, Balawi was outfitted with a suicide vest containing thirty pounds of C4 explosives and shrapnel. Ball bearings and nails. He was delayed by over twenty-four hours because the Taliban wanted to extract more propaganda mileage out of his suicide bombing, and made him record multiple videos.

Balawi himself appeared to have regretted the path his life had taken, and tried, in his last days, to avoid becoming a suicide bomber. He was concerned about premature detonation, not about killing the people he would be meeting. But al-Qaeda and the Taliban both saw him as a means of exacting revenge upon the CIA for drone strikes that had killed scores of terrorists in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Nine other people lost their lives in the attack, including Captain Sharif Ali bin Zeid, the Jordanian handler. He was a cousin to King Abdullah II of Jordan, and his wake was held in the Royal Palace at Amman.

The attack was dramatised in the film Zero Dark Thirty.

Pakistan

A heavily redacted secret State Department cable (PDF link) written in early 2010 claims that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence funded the attack.

An unidentified ISI officer met Haqqani and handed over $200,000 to enable the attack on FOB Chapman.

The contents of the cable was described by a serving US Intelligence official, however, as an “unverified and uncorroborated report”.

About the title

Looking back now, the title seems frivolous considering the human tragedy narrated here. But the fact remains, Humam al-Balawi pulled the wool over the eyes of two very competent intelligence agencies.

Ordinarily, he would have been investigated by CIA’s counterintelligence team. But with the war on terror stretching resources thin and piling pressure on CIA leadership, the practice appears to have been abandoned somewhere between the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

This same pressure to deliver results led to Balawi being allowed to dictate terms. Otherwise he would have been searched by the security team outside the base, the suicide vest would have been detected, and the fatalities would have either been avoided altogether, or would have belonged to the Afghan Army.

Later, several former intelligence officials expressed surprise at the manner in which a potentially hostile double agent was allowed into close proximity to so many CIA officers.

I have never heard of anything as unprofessional. There's an old infantry rule: Don't bunch up.

—A former CIA case officer

If you enjoyed reading this post, you will love reading my spy novels.

The Let Bhutto Eat Grass series deals with nuclear weapons espionage in 1970s India, Pakistan, and Europe.

The Triple Agent by Joby Warrick is a detailed account of Humam al-Balawi’s journey from Amman to Khost, and the attack on FOB Chapman.