People's Republic of Big Data, circa 1952

The US recruited a Chinese interpreter during the Korean War. 30 years later the CIA gave him the ‘Career Intelligence Medal’. 5 years after that he pulled a plastic bag over his head.

Shenzhen Zhenhua Data Technology, a Chinese firm, has been caught collating and analysing all kinds of online data about more than two million people of interest to the People’s Republic of China. This cache of intelligence is called the Overseas Key Information Database, or OKIDB. It enables users to gain insight into foreign leaders — political, military, and business — as well as understand military deployments and public opinion. The Chinese military & the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) are believed to be the primary consumers of this data, and have compiled similar data before according to Anne-Marie Brady, a professor at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand:

The CCP and China’s Ministry of State Security has long compiled country-by-country information about foreign economic and political elites, and foreigners who had lived in China for any period. I’ve seen whole books outlining the careers and political views of US China experts.

The value of the data itself has, however, been downplayed by some analysts. As the Washington Post reports:

Swaths of the database appear to be raw information copied wholesale from U.S. providers such as Factiva, LexisNexis and LinkedIn and contain little human analysis or finished intelligence products. Much of the social media trove appears to be scraped from public accounts accessible to anyone.

This isn’t worthless information, though, and can be used to build a revealing profile of the people involved for disinformation and influence operations, bribery, etc. There are many examples in history of intelligence agencies paying agents to gather similar information at a smaller scale.

The Abwehr, Germany’s military intelligence agency during the second world war, wanted one of their main agents in Britain to get them answers to the following questions:

Who are the people opposed to Churchill and working for peace with Germany? How can they best be approached? Who are their contacts? What are their hobbies and weaknesses – money, drink, et cetera? What kind of propaganda would be most effective? Which class of people is most susceptible to propaganda and how can they be best approached?

And this is not out of character for Chinese intelligence efforts either. Historically, the PRC’s approach to acquiring intelligence has differed significantly from that of US or Soviet agencies. The data collated in the OKIDB fits neatly into the approach the MPS has taken towards intelligence gathering — often described as ‘holistic’ — since at least as far back as 1952.

Korean War

Korean war

Chinese troops crossed the Yalu river on 19 October 1950, four months after the Korean war began. As the conflict progressed, the United States was capturing Chinese soldiers faster than they could be interrogated. Chinese-speaking interrogators were in short supply. One of the people recruited to address this was Larry Wu-Tai Chin, who had worked for the U.S. consulate in Shanghai before the formation of the People’s Republic of China.

Born in China in 1922, Larry had studied English & Journalism at Yenching University, Beijing. He served from 1952 with the US Army in Korea and the consulate in Hong Kong. His job was to interview Chinese prisoners captured by US and South Korean troops. During these interviews, he came across several Chinese troops who did not wish to be repatriated to China after the war. He also came to understand what kind of intelligence American and South Korean intelligence officers wanted from these prisoners.

Hong Kong in the 1950s

When Armistice negotiations were proposed to bring the Korean War to an end, China and North Korea demanded the repatriation of their soldiers who had been captured. As negotiations progressed in 1952, the Chinese and North Koreans appeared resigned to a few soldiers refusing repatriation. But then the negotiations stalled.

Dr Wang

It was during this period that Larry began going to a nondescript flat in Hong Kong after work to meet “Dr Wang”. He had known Dr Wang since 1948 when Larry was working at the US consulate in Shanghai. There they would talk about American interrogation techniques as well as the prisoners Larry had helped interrogate, particularly those prisoners that were volunteering information and those that did not seem inclined to return to China. Many were believed to be keen on going to Taiwan.

Dr Wang worked for the MPS. Before the creation of the Ministry of State Security (MSS) in 1983, it was the MPS that was responsible for gathering domestic and foreign intelligence. Dr Wang was Larry’s case officer.

Dr Wang did not look anything like this MSS case officer (left)

There were no requests made by him for specific information. No questions like “We would like to know more about X” or “Tell us how the Americans hope to accomplish Y” that one would expect to have marked meetings between agents and their case officers. He was content to be a patient listener, and paid Larry $2,000 for eclectic information that Larry chanced upon in the process of doing his official job.

Which is not to say that the MPS was throwing its money away. China made excellent use of this intelligence. They delayed negotiations and prolonged the war by more than a year, insisting that all their soldiers be repatriated even as the US stuck to its guns about not allowing forced repatriation of unwilling prisoners of war. At the end of it all, those soldiers who had been identified by Larry but later agreed to repatriation suffered severely upon arrival in China.

Okinawa

Radio monitoring station; not Larry Wu-Tai Chin

Larry was a competent interpreter and soon found himself employed by the CIA. He was based in Okinawa, monitoring Chinese radio broadcasts. During this time, based on the radio intercepts he had been asked to translate, he became familiar with the kind of intelligence the CIA sought. Occasionally, he’d take a week or two off to visit family back in Hong Kong, sending postcards in advance to alert his handler to his arrival. Then, at a suitable time, he would go to Dr Wang’s apartment. The two of them would talk for hours about the information Larry had purloined.

Dr Wang’s reports of these conversations enabled the MPS to check the CIA’s ability to gleam intelligence from public broadcasts. If Larry indicated that the CIA were particularly interested in information about a particular aspect of the Chinese economy, for example, the MPS would curtail its public release while ramping up disinformation efforts, feeding the CIA garbage data.

Once again it wasn’t the MPS case officer pointing Larry in any particular direction. The information collected by the spy was determined by circumstances of his own job.

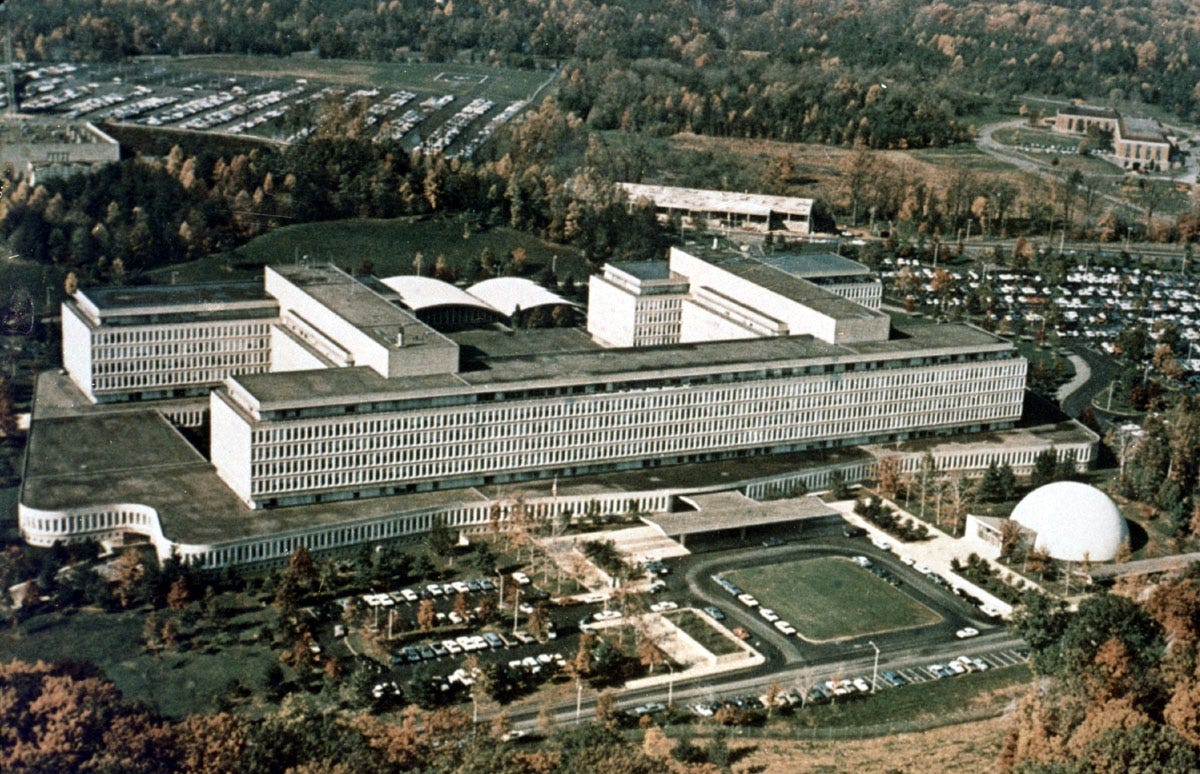

United States

CIA headquarters in Arlington

In 1961 he moved to California and in 1970 to Arlington, Virginia. His handler changed. Larry’s responsibilities at the CIA had widened from just prisoner interrogations to the translation of intelligence. Not only was he reviewing Chinese documents received by the CIA from its agents, he was also helping translate instructions from the CIA to those same agents. And now he had access to classified information.

He often asked for details about the agents themselves so that he could choose the appropriate words for translating instructions. His questions pertained to the agent’s location, age, gender, level of education, etc. Nobody suspected anything because of the nuance-rich nature of Cantonese and Mandarin.

The importance attached to Larry by the MPS can be gauged from the fact that the MPS even prepared an escape plan for him. In case of an emergency he was to meet Mark Cheung in a confessional booth. Cheung’s cover story was that he was a priest at the Church of the Transfiguration in Chinatown, New York, but in fact he was a Chinese illegal, a sleeper agent whose only job was to hide Larry from American authorities and help smuggle him out of the US if needed. Larry was also assigned a handler in Toronto, a “Mr Lee”.

Larry began frequenting casinos and strip clubs. Think Leisure Suit Larry. And he made no attempt to hide this from his colleagues. Over time he acquired a reputation of being a successful gambler. Many of his colleagues who had, at some time or the other, visited a casino with him could recall at least some instances of him winning significant sums of money. As money from China rolled in, it began showing in his lifestyle. But he was able to attribute all this to winnings from gambling. And his colleagues accepted the explanation.

Nixon

While working at Arlington, Larry came across a document that outlined Richard Nixon’s plan of visiting China and opening relations with that country. It was a memo sent by Nixon to the United States Congress and contained details about what Nixon hoped to achieve. Larry smuggled the document home and photographed it, then called his handler in Toronto. A few days later he flew to Buffalo, NY, rented a car and drove to Toronto, handed the roll of film over to his handler, and returned to Arlington.

The photographs found their way to Mao’s desk. The plans contained within, pieced together with the profile the Chinese had developed for Richard Nixon and his team from other intelligence sources, helped convince Mao that Kissinger’s request for a meeting wasn’t a trap nor was it meant to be an insult. As the Chinese realised that they could anticipate Nixon’s planned moves, they felt comfortable enough to engage with Nixon on their terms and negotiate for what they wanted.

Retirement

Larry was paid handsomely for this and other information. Over the course of 30 years the Chinese paid him $180,000, the equivalent of more than $1,000,000 today. He was never given money at meetings with his handler in Canada; it was deposited in bank accounts in Hong Kong. He used some of that money to buy apartment buildings in Baltimore, becoming a slumlord with a sizeable passive income.

Career Intelligence Medal

Larry retired in 1981 and was awarded the Career Intelligence Medal by the CIA. After his retirement, he continued gathering bits and pieces of information. He would call up his old subordinates and ask innocuous questions like where they were currently working, who their boss was, etc. And he continued providing this to his handler. The MPS remained oblivious to news of his retirement. The Chinese even honoured him with a banquet in Beijing in 1982.

In the early 1980s, the CIA was approached by a senior Chinese intelligence official. Yu Qiangsheng was working for the MPS and later a Director with the MSS. His parents had been communist revolutionaries, and his brother was a rising star in the CCP. He is believed to have been a “walk in”, a foreign intelligence official who approaches a rival government and offers to spy for them.

China’s Ministry of State Security or MSS

In March 1982 Yu told the CIA that the American security establishment had a Chinese mole who had provided intelligence to Yu’s organisation for thirty years. He had never worked with this agent and did not know his name, but he had heard about him from others. He also mentioned that this mole had recently travelled to Beijing. The CIA took six months to hand the information over to the FBI for a counterintelligence investigation.

Counterintelligence Investigation

Yu had mentioned that the agent had travelled from the US to Hong Kong on 6 February 1982 on a Pan Am flight from Dulles. The FBI began searching for passenger manifests for all Pan Am flights that departed from Dulles for Hong Kong that day, and immediately hit a dead end: Pan Am did not maintain detailed lists of passengers for each flight.

The FBI took another approach, combing through check in lists, first for Pan Am, and then for the entire airport for that day — tens of thousands of records — and noting down any names that sounded Chinese. These were then cross-referenced with names of government employees maintained by the FBI in its own databases. They found their suspect in January 1983 with a passenger that had flown CAAC Airlines, the monopoly civil aviation airline in the PRC.

Despite further investigations involving the work Larry had done while he was employed, the FBI were unable to gather definitive proof. So, in 1983 they had the CIA reach out to Larry and ask him to return to active duty. The idea was to monitor him in the office, feed him false information, and wait for him to pass it to the Chinese. But Larry refused, citing philanthropic work as an excuse.

The FBI bugged Larry’s apartment and began monitoring his mail. It went on for two years during which the FBI learnt that Larry was a vile domestic abuser who also enjoyed phone sex with professionals who he liked to call his “nieces”. Larry was also accused of assaulting teenaged girls at least twice while he was under surveillance.

The FBI believed they had made a breakthrough when they recorded a phone conversation between Larry and a woman. Larry asked her to bring “the machine” when she visited him. But with more conversations full of salacious details they finally concluded that the machine Larry hoped she would bring for their rendezvous was a sex toy.

Breakthrough

In June 1984 Larry travelled to Hong Kong. The FBI had learnt about this trip from their wiretaps and were prepared. At the airport, his check-in baggage was taken aside and every item in it was inventoried and photographed. The bag was then packed just as Larry had initially packed it and rushed to the aircraft. They found a rather unique key with a few Chinese characters on it and the number 533. Nothing else stood out.

After translating the characters and doing a bit of research, the FBI found out that the key belonged to a hotel room. Yu confirmed that the hotel was frequently used by Chinese spies for meetings. But this wasn’t enough to charge him. As 1985 came along, the FBI was getting frustrated. They had gathered bits and pieces of information that convinced them Larry was a spy, but the evidence was inadequate to prosecute him.

They finally decided to call him in for an interview and forcefully confront him with some of the details they had, hoping he would let slip some incriminating detail. They revealed some of the details that Yu had given them while giving Larry the impression that there was lot more evidence against him. But it was when they mentioned the hotel and room number that Larry cracked and agreed to tell them everything.

Larry Wu-Tai Chin

The FBI later recovered, among other things, a diary Larry had maintained. It contained detailed descriptions about his meetings with Chinese intelligence officials, and the trips that he went on with them while in Beijing. On one such trip Larry had dined on bear’s feet.

On 8 February 1986 Larry was sentenced to 133 years in prison for espionage and tax evasion. In an interview to CBS, Larry suggested that he would request Deng Xiaoping for a prisoner exchange.

I didn't realize I was going to be in jail for the balance of my life.

He ate breakfast at 6:30am on 22 February 1986 and was found dead at 8:45am. He had suffocated himself using a plastic bag used in prison for collecting garbage.

If you enjoyed reading this and would like to read more, subscribe to Espionage& on Substack using the button below.

You’ll also enjoy reading my spy novels: Let Bhutto Eat Grass & Let Bhutto Eat Grass: Part 2 deal with nuclear weapons espionage in 1970s India, Pakistan, and Europe.