Cyclone

The beginning of the 1970s was a period of calamities for East Pakistan. The Bhola cyclone struck on 11 November 1970, with sustained winds of 240 km/h causing a 10 m storm surge in the Ganga delta. 3.6 million people were directly affected, and 300,000 to 500,000 were killed.

General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan, the President of Pakistan and proud owner of sentient eyebrows, visited East Pakistan on his way back from China. After downing a considerable volume of beer, he promptly declared that the damage caused by the cyclone had been blown out of proportion, and returned to Rawalpindi. Other leaders from West Pakistan didn’t even bother to visit the part of their country that was home to 55% of its population.

Over the next ten days, Pakistan devoted a sum total of one military transport aircraft and three crop-dusters to relief efforts directed at a population of 65 million. Political leaders in East Pakistan were deeply critical of this neglect, and while Yahya later tried to make amends, it was too little too late.

Despite the tragedy that had befallen more than half its population, Yahya insisted on proceeding with general elections on 7 December.

Election results

Out of 300 National Assembly seats that went to the polls, East Pakistan’s Awami League, headed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won 160. But since his party hadn’t won a single seat in West Pakistan, his opponent — Zulfikar Ali Bhutto [after whom my series of spy novels is named] claimed Mujib had no mandate to rule Pakistan. This argument neatly ignored the fact that Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party hadn’t won a single seat in East Pakistan.

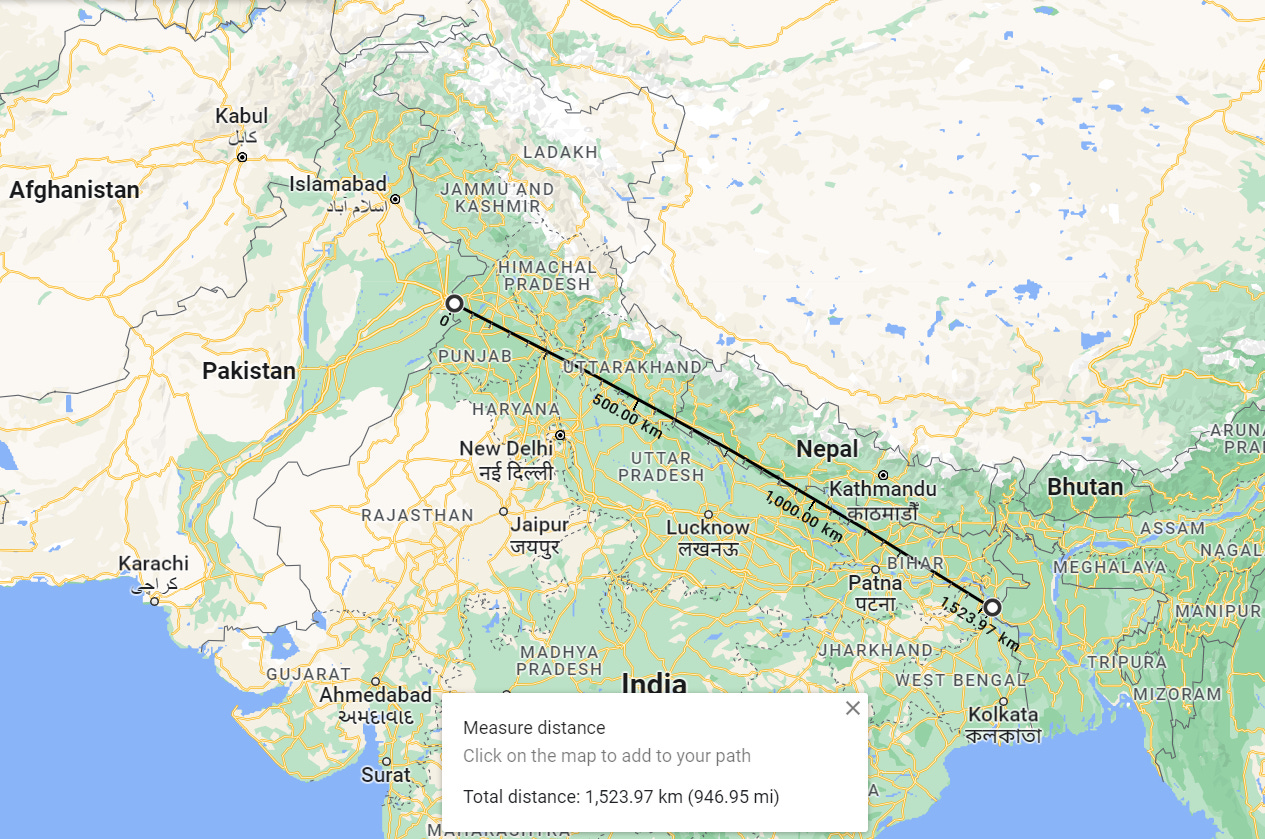

Yahya and Bhutto did not want the Awami League forming the national government and spent the months after the elections manoeuvring towards that end. As it became apparent that West Pakistani leaders had no intention of peacefully transferring power to the Awami League, sparking unrest in East Pakistan, the government began confronting the logistical challenge of containing popular anger: East and West Pakistan were separated by more than 1,500km of Indian territory.

Ganga

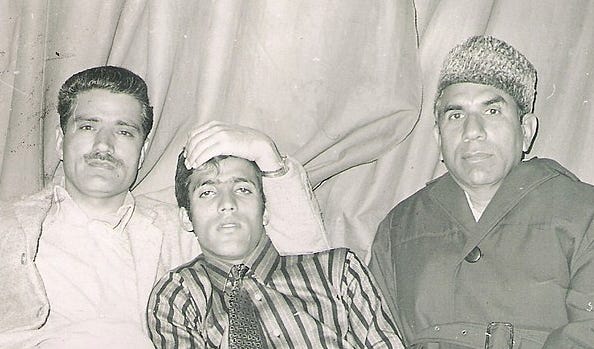

On 30 January 1971, two Kashmiri separatists — Hashim and Ashraf Qureshi — belonging to the National Liberation Front (NLF) were flying on ‘Ganga’, a Fokker F-27 Friendship 100 belonging to Indian Airlines, from Srinagar to Jammu. There were 24 other passengers flying with them.

As the aircraft prepared to land, one of them — Hashim, perhaps — rushed to the cockpit and used a handgun to threaten the pilot, Capt. Kachru. The other stood in the passage brandishing a hand grenade (or a stick of dynamite, depending on the source). Together, the two separatists hijacked the aircraft and had it diverted to Lahore in Pakistan.

At Lahore, the Qureshi cousins were welcomed like heroes. They demanded the release of 36 NFL separatists imprisoned in India, but succumbed to pressure from Pakistani authorities and released passengers and crew.

Hashim, who was the more flamboyant of the two, was allowed to roam around freely, and given access to the telephone and the press. Ashraf remained on the aircraft. Later, Bhutto showed up at the airport and showered the hijackers with fulsome praise.

Every significant political leader in Pakistan condemned the hijacking. Everyone, that is, except Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. This lent credence to India’s claims that the Pakistan government was involved in the hijacking.

Since the passengers and crew were safe, the Indian government refused to heed the hijackers’ demands, triggering a standoff that lasted for eighty hours. During this time, the aircraft remained on the tarmac. Pakistani security forces performed a thorough search of the aircraft.

Time ran out. On the advice of Pakistani authorities, Hashim and Ashraf set fire to the aircraft

Overflights

India wasn’t too pleased but Pakistan appeared delighted. The Qureshi brothers were lauded as heroes in that country. India seized upon the burning and the hero’s welcome to ban all Pakistani overflights across its territory.

West Pakistan’s logistical challenge had just grown by a magnitude, with its aircraft now forced to fly via Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), a detour of more than 4,600km.

Pakistan Air Force C-130J Hercules aircraft had to refuel in Ceylon, and even then, they were stretching it.

When Pakistan realised what had happened, they turned on the hijackers and arrested them and their collaborators. An investigation by a judge concluded that the hijacking was a conspiracy by India. Hashim Qureshi was convicted and sentenced to 7 years in prison, but Ashraf was acquitted because of a deal made by Bhutto.

Pakistan took the issue of overflights to the UN Security Council, charging India with an ‘act of belligerence.’ But India was in no mood to relent, and the overflight ban remained in place.

This left Pakistan hamstrung in its efforts to move sufficient troops and equipment from West Pakistan to East Pakistan. It then launched Operation Searchlight, a genocidal campaign against the Bengalis that made up a majority of the East Pakistani population, in March 1971. Over ten million refugees fled to safety in neighbouring India.

The genocidal regime would kill 3 million Bengalis before it ended.

The Indian government then intervened in December, with the Indian Army and the Mukti Bahini — Bengali partisans — routing the Pakistan Army in East Pakistan in a blitz that lasted all of 13 days. In the end, the commander of Pakistani forces in the East, Lt. Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, surrendered to the Indian Army.

The Indian Army took 93,000 prisoners of war.

The many faces of Hashim Qureshi

There was more to Hashim Qureshi, of course, than met the eye. For starters, there are reports that before the hijacking, he worked for Indian intelligence, crossing over into Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) and infiltrating the separatist NLF. It was reported later that Qureshi was ‘turned’ by Pakistani intelligence and sent back to Kashmir with instructions to hijack an aircraft. Rumour has it he was supposed to hijack an Indian Airlines aircraft piloted by Rajiv Gandhi, the son of then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

As he tried to infiltrate back into Kashmir, India’s Border Security Force apprehended Qureshi at the Line of Control (LoC). The handgun and explosives he was carrying were confiscated. And under intense interrogation, Qureshi reportedly broke and revealed the Pakistani plan. He was then persuaded to ‘turn’ once again.

They then ordered him to hijack an Indian Airlines aircraft flying from Srinagar to Jammu and gave him a wooden handgun and a fake hand grenade to accomplish it. His orders were clear: he wouldn’t hand over the aircraft to Pakistani authorities unless Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came and met him. And once that was accomplished, he was to destroy the aircraft.

A few days before the hijacking, a retired Fokker F-27 Friendship 100 aircraft of Indian Airlines was re-inducted into service on the Srinagar-Jammu route. And that is how Hashim and Ashraf Qureshi hijacked the ‘Ganga’ and prevented Yahya Khan from moving enough troops to crush the rebellion in East Pakistan.

Hashim Qureshi has refuted these reports, but his mentors in the NLF — G. M. Mir and Ghulam Mustafa Alvi — claimed that they were certain he worked for Indian intelligence. But since he had hijacked an aircraft and used their separatist movement’s name, they felt morally bound to support him.

The plan to hijack the aircraft had been conceptualised by Maqbool Bhat, founder of the NLF, but Indian intelligence ended up, pardon the pun, hijacking it.

If you enjoyed reading this post, you will love reading my spy novels.

The Let Bhutto Eat Grass series deals with nuclear weapons espionage in 1970s India, Pakistan, and Europe.

This was a fascinating read! Thanks for this, Shaunak!

I am actually binge reading all of your substack posts, incredible stuff. Cheers🍻