The reticent Director of the CIA

About the brave men who warned a future Director of Central Intelligence about the Holocaust as it was happening, and how he completely ignored it.

If you enjoy longform posts about real spies, please consider sharing this post — and this substack — with friends and family. I have also written a highly acclaimed series of four spy novels set in India, Pakistan, and Europe during the Cold War. You can check it out on Amazon. If you would like to support my substack, buy me a cup of coffee here.

The nerve centre

The Blomberg–Fritsch affair was two scandals used by Hitler, Göring, and Himmler in 1938 to subjugate the German Armed Forces. Werner von Blomberg, who was the Minister of War and an ardent supporter of the Nazi regime, was coerced into resigning days after his second marriage after it emerged that his 24-years-old wife, Erna Gruhn, had posed for pornographic photographs six years earlier. Buoyed by this success, Göring and Himmler resurrected an old file on Werner von Fritsch, who was the Commander—in-Chief of the German Army. The file accused him of homosexuality.

When von Fritsch resigned, Hitler seized the opportunity to reorganise the German Armed Forces. A new organisation — Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) or Supreme Command of the Armed Forces — was created, and the duties of the Ministry of War were transferred to it. Over the course of the Second World War, the existing Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) or Army High Command was weakened and made subordinate to OKW. OKW coordinated the efforts of the army, navy, and air force.

The diplomat

1925 was an eventful year for Fritz Kolbe. The twenty-five years old former stationmaster got married and joined the Foreign Office in Berlin, beginning a career more eventful than his wildest dreams. Soon afterwards, he was dispatched to Spain, where he would remain until the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. When the Nazis assumed power in Berlin, all his colleagues joined the party. Despite pressure from his superiors, Kolbe declined to become a Nazi. A longish stint in South Africa followed. He was called back to Berlin at the outbreak of the Second World War.

As the war progressed and the Foreign Office became more and more nazified, a despairing Kolbe considered fleeing across the border to Switzerland. But his friend Prelate Georg Schreiber, head of the monastery at Ottobeuren in Bavaria convinced him to work against the nazis while remaining inside the government. Because he was excellent at his job, Kolbe became indispensable to Rudolph Leitner, and the latter protected him from being purged.

In 1941, Kolbe began working for Karl Ritter, who was assigned as liaison between the Foreign Office and OKW. And because Hitler began spending most of his time at the Wolfsschnaze, his Eastern Front Military Headquarters in East Prussia (now Poland), senior Foreign Office officials — including Ribbentrop, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Karl Ritter — were also accommodated nearby in a headquarters of their own. Ritter was one of many German diplomats who had not been able to resist the pressure to join the party.

Because Ritter was often at Wolfsschanze, more than five hundred kilometres from the rest of the Foreign Office in Berlin, it fell to Kolbe to review incoming diplomatic cables and diplomatic reports, and flag important ones for Ritter. Many of these cables and reports involved military affairs.

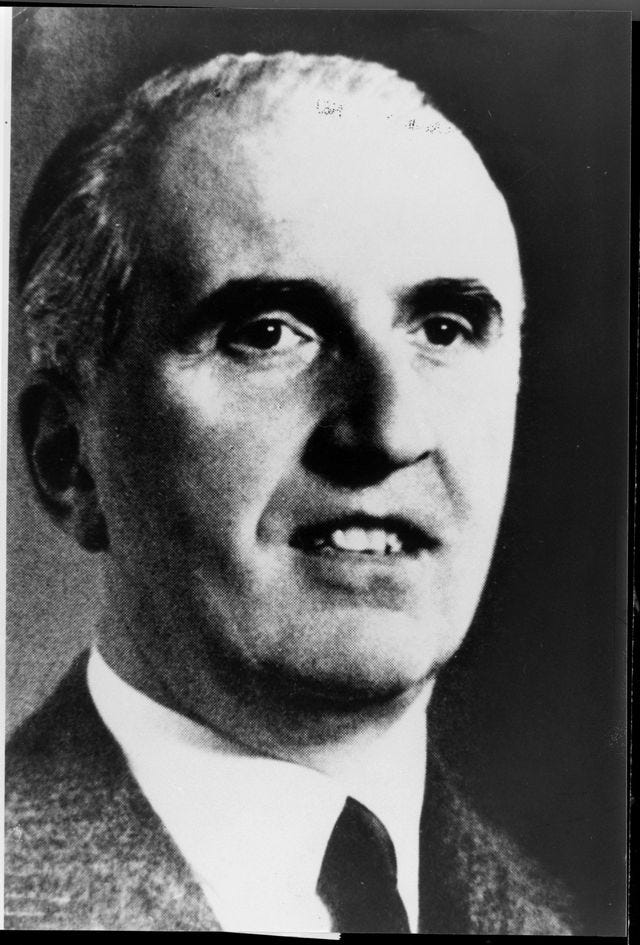

The reticent spook

In November 1942, Allen Dulles flew from New York to Lisbon. There, he met an old friend, Thomas McKittrick, who was president of the Bank of International Settlements (BIS). The two of them stayed up all night at their hotel exchanging information. So crucial was the BIS to Nazi Germany’s war effort that Emil Puhl, the Vice President of the Reichsbank, called it their only foreign branch.

Dulles then hopped over to Barcelona before boarding a train for Geneva. He carried with him a $1 million letter of credit, and a code book. The train passed through Vichy France, and passports were inspected just before the Swiss border. After a German Gestapo officer noted details from his passport, a French gendarme explained that they had orders to detain all American and British citizens at the frontier. Half an hour later, as the train was about to depart and the Gestapo officer was away, the same gendarme urged Dulles to hop back on, assuring him that their cooperation with the nazis was symbolic. Critics believe Dulles’s retelling of the border crossing was heavily embellished.

Dulles had been sent by William “Wild Bill” Donovan, the Director of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) — the precursor to the CIA — to set up the OSS’s operations in Bern. Donovan had initially planned for London to be the base of operations, but Dulles had fiercely argued in favour of Bern, ostensibly because it was neutral and therefore crawling with Nazi spies. It didn’t hurt that Switzerland was the financial conduit for Nazi Germany’s war machine.

And he had clients to protect. Sullivan & Cromwell, the firm his brother John Foster Dulles led — and in which Allen Dulles himself was a partner — had numerous corporate clients in Germany, including I. G. Farben (who would supply Zyklon B to the Nazi regime for use in their gas chambers). They also had a number of American clients who had sizeable corporate assets in Germany. By establishing himself in Bern rather than London, it would be possible for Dulles — with McKittrick’s help — to safeguard these assets from the US government.

Unlike others in the espionage business, Dulles made no effort to maintain a low profile in Bern. His arrival was reported in Swiss newspapers, which called him “the personal representative of President Roosevelt”, he set up his base of operations in a magnificent mansion in the heart of the city, and he met his informers openly in the city’s cafes. He wasn’t very effective at the security aspect of running an espionage operation either. The staff who worked for him at the mansion on 23 Herrengasse — the cook and the janitor — spied on him for the Nazis and stole copies of his documents.

The businessman

A tall German businessman with a prosthetic leg alighted at Zurich railway station on 29 July 1942. Eduard Schulte had travelled from Breslau, where he ran a zinc mining company, barely two weeks after Heinrich Himmler’s private train arrived at Auschwitz in Poland. Although he wasn’t a member of the Nazi party himself, Schulte’s company had made a company-owned villa available to the local Nazi chief. Himmler had stayed at that villa while at Auschwitz, which is why Schulte had found out about Himmler’s visit. But Himmler’s presence there hadn’t made much sense to Schulte. Auschwitz wasn’t considered large enough or important enough a Polish town to merit the attention of the Reichsführer of the Schutzstaffel, the commander of the dreaded SS. He would learn the significance of Himmler’s visit on 27 July, twenty-four hours before he risked everything to travel to Zurich.

This wasn’t the first time he had travelled to Zurich, of course, and he checked into his usual luxury hotel by the lake to mantain an appearance of normality. There he met Isidor Koppelman, a Jewish investment adviser, and revealed what he had learnt about Himmler’s visit. The Reichsführer had travelled to Auschwitz to witness the operation of Bunker 2, a gas chamber at the prison camp. He had watched as 449 Jews were marched into Bunker 2 and gassed with Zyklon B, manufactured by I. G. Farben. He had stayed through the twenty-minutes-long execution process, hearing their screams through the thick walls, and watched as men wearing gas masks later dragged their bodies to the incinerator whose heat was utilised by the I. G. Farben factory built to utilise Auschwitz’s slave labour. After asking Koppelman to somehow get this information to the Allies, Schulte checked out of the hotel and took the train back to Germany.

The unheard message

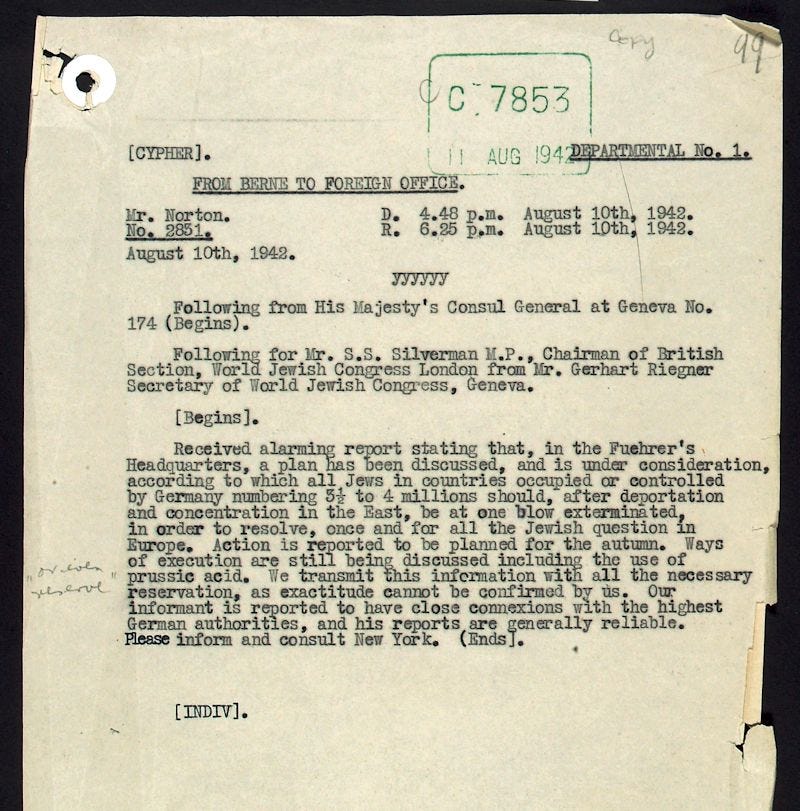

Koppelman managed to get Schulte’s information to Gerhart Riegner, the Geneva representation of the World Jewish Congress (WJC). Reigner sought to transmit his report to Rabbi Stephen Wise, the president of the WJC in New York, and approached the British representatives and the American Legation in Bern on 8 August. The State Department representatives in Bern took a sceptical view of Riegner’s account. While transmitting it to headquarters, they added comments to the cable critiquing it as nothing more than rumours. In Washington D.C., the State Department employee who received the cable wasn’t overly fond of Rabbi Wise — considered by Foggy Bottom to be a thorn in its side — and did not inform him. The State Department did not inform President Roosevelt either.

The report transmitted through British diplomatic channels eventually found its way to Rabbi Wise on 28 August. When Foggy Bottom interfered with Wise’s efforts to raise the issue with Roosevelt, the frustrated Rabbi held a press conference on 24 November. Hitler had already killed two million Jews and planned to kill the rest, he announced. The New York Times carried the story on page 10, giving the excuse that it hadn’t been corroborated by the government (read Foggy Bottom).

Around the time Reigner was trying to draw the attention of the Allies to Schulte’s report, Dulles was in New York, dispatching reporters to various parts of Europe with diplomatic cover to gather intelligence. One of those — Gerald Mayer — sent report after report to Dulles about Hitler’s Final Solution. One such report began with stunning clarity:

“Germany no longer persecutes the Jews. It is systematically exterminating them.”

This was clear corroboration of Schulte’s account transmitted to the US government through Reigner. Dulles ignored it.

Later that year, he moved to Bern, and a few months later, he met Schulte in Zurich. The German had heard more accounts about the Final Solution, and urgently repeated his concerns about Hitler’s extermination of Jews. But if Schulte thought explaining all this in person would somehow yield different results, he was grossly mistaken. Dulles wasn’t interested in what Hitler was doing to the Jews at all. Instead, he asked Schulte to characterise the mood of the German people and how the Allies could win over their loyalty.

The diplomat, again

Earlier, before Perl Harbour, Fritz Kolbe had tried — through intermediaries in the Catholic church — to reach officials in the American embassy in Berlin. But after Germany declared war, the embassy was shut down and Kolbe had no means of initiating contact. By the time the spring of 1942 came along, as Germany’s fortunes on the Eastern Front ebbed and flowed, Kolbe decided to make another attempt. He put in a request to be allowed to vacation in the Swiss Alps. His superiors turned him down.

Kolbe was dejected, but he didn’t give up. When he read in a cable from the ambassador to Vichy that the Archbishop of Lyon, Cardinal Pierre-Marie Gerlier, was about to be arrested because he had intervened to save many Jewish children (he had asked Roman Catholic institutions to take Jewish children into hiding), Kolbe made contact with the resistance in Alsace and had them warn the French Resistance.

The year after that, he sought permission to go to Switzerland once again. He needed to divorce his wife, he told his superiors. And since she was Swiss, he needed to engage an attorney in Zurich. They told him it wasn’t important. Finally, in August, he finagled an exit visa through a friend in the Foreign Office, Maria von Heimerdinger. She was the assistant chief of the courier section, and assigned him the task of carrying a diplomatic pouch to Bern the following week. In addition to the pouch, Kolbe had a bundle of secret documents strapped to his leg as he took the train to Switzerland on 15 August.

Kolbe first made contact with the British through an intermediary, Dr. Ernest Kocherthaler. The British listened to what Dr Kocherthaler had to say, and then politely showed him the door. Kocherthaler now realised that in order to succeed with the Americans where he had failed with the British, he would need an introduction from someone the Americans trusted. So he wrote to Paul Dreyfus, a Basel-based banker. Dreyfus introduced him to Gerald Mayer, who had warned Dulles many times about the Final Solution.

Although wary, Mayer was impressed by the German diplomatic cables Kocherthaler showed him. When Mayer told Dulles about them, the spymaster decided to accept the risk and meet Kocherthaler and his source. During a prior stint in Bern, a Russian emigre had sought to meet him. But Dulles had a pre-scheduled tennis game to rush to, and offered to meet the emigre the next morning. That was, of course, too late, because by then Vladimir Lenin was on a German train headed for Russia. Ever since, Dulles had made it a point to meet potential sources at the earliest.

The reticent spook, again

Shortly after midnight on 18 August, Dulles and Mayer met Kocherthaler and Kolbe at Mayer’s apartment. Kolbe told Dulles and Mayer all about himself, and explained how working for Ritter gave him access to secret diplomatic cables. Then, over the next several hours, he opened up the secrets of the German war effort to the Americans, briefing them about conditions in Germany, the complete collapse of long-term planning in the German war industry, the results of Allied bombing on certain German factories, the number of German divisions in Greece and Sicily, the order of battle of the Luftwaffe, the names and locations of several German spies in Allied countries, and details of Sicherheitsdienst (intelligence arm of the SS) and Abwehr (German military intelligence) operations in many different countries.

And he told them about the concentration camps.

Over the next three years, Kolbe went back to Bern twice a year. Each time, he carried a treasure trove of secret documents for Dulles. By the end of the war, he had shared more than one thousand six hundred diplomatic cables with American intelligence.

In April 1944, he drew Dulles’s attention to a sheaf of diplomatic cables and warned that Jews in Hungary, who had remained safe until then, were about to be rounded up and exterminated. He urged the Allies to bomb the rail tracks and infrastructure leading to concentration camps. That, he assured Dulles, would foil the German effort and secure Jewish lives. Dulles’s report about this meeting with Kolbe reached the president. It spoke of Kolbe’s apprehension that underground communist movements were becoming stronger in Germany as the nation’s fortunes waned. The threat to Hungary’s Jews did not merit mention.

In the following months, Kolbe supplied cables detailing imminent Nazi plans to deport hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. Instead, Dulles’s reports to Washington spoke of them being conscripted.

“Why did Dulles choose not to emphasize the Holocaust in his reports to Washington? Whatever his reasoning, his reticence on this subject is among the most controversial and least understandable aspects of his performance in Bern.” —Neal H. Petersen, World War Two historian

If you enjoyed this post and would like to dive deeper, among other things, into the Dulles brothers’ suspected Nazi sympathies, “The Devil’s Chessboard” by David Talbot will make for an infuriating read.

You can support this substack by buying me a cup of coffee using the button below, and by buying my novels on Amazon.