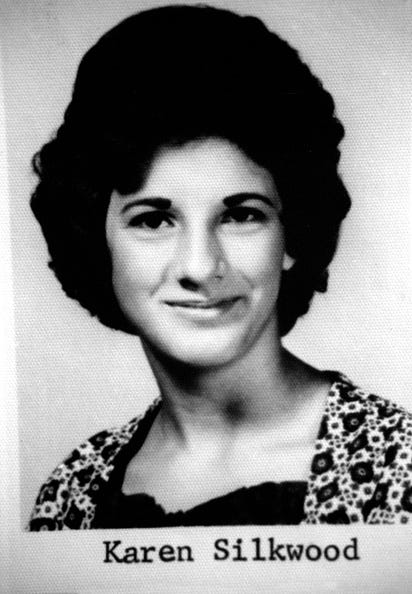

The Death of Karen Silkwood — Part One

The plutonium plant employee highlighted lax safety protocols and investigated faked quality control data, making a frightening discovery in the process.

[As Espionage& stories go, this one is a long read even though I’ve split it into two parts. The narration draws heavily from The Killing of Karen Silkwood by Richard Rashke, besides a few other sources enumerated at the end of the second part. Unless otherwise stated, all quotes are from Rashke’s excellent book.]

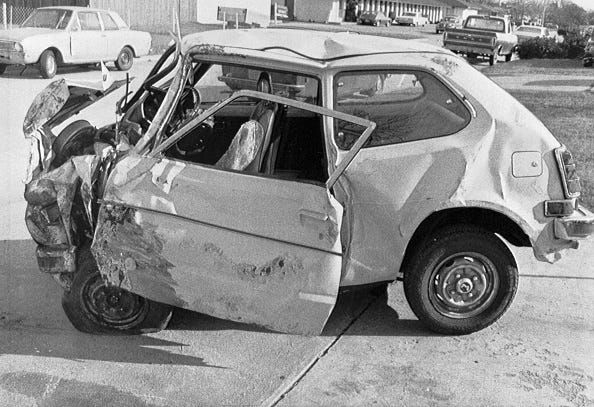

A little before 7:30 on the evening of 13 November 1974, a white Honda Civic headed for Oklahoma City on State Highway 74 ran off the road and crashed into the culvert. The sole occupant, a 28-years-old woman named Karen Silkwood, was rushed to the nearest hospital, only to be declared dead on arrival.

The I.D. badge in her pocket said that she was an employee of Kerr-McGee, a billion dollar energy company with operations in that region. After quiet suggestions from company management, the police soon concluded — tentatively — that it was an ordinary accident caused by Silkwood falling asleep at the wheel.

The autopsy would buttress this conclusion by pointing out that Silkwood had sedatives in her bloodstream. But that report would arrive a few days later. For now, the police had her car towed to a garage.

But unlike other accidents, there were a couple of aspects that immediately made this fatal one-car crash extraordinary.

Later that night two teams in protective clothing descended on the garage to examine the car. The first set of men were from Silkwood’s employer, the Kerr-McGee Cimarron Fuel Fabrication Site in Oklahoma. The second set was from the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). And at the time of her death, a New York Times reporter was waiting to meet Karen at a hotel in Oklahoma City.

Strike, personal problems, and contamination

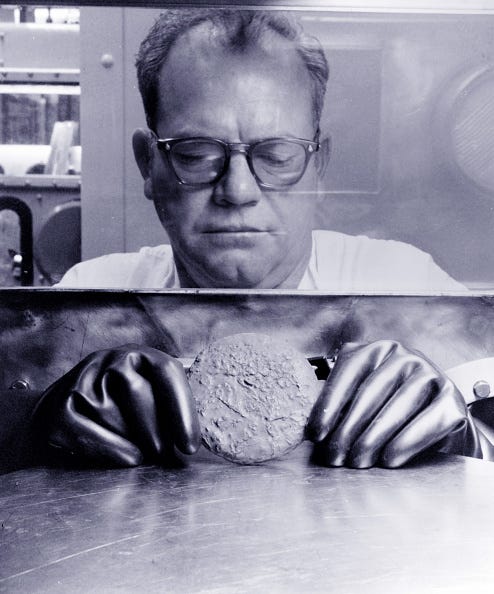

The Cimarron facility manufactured plutonium pellets for nuclear reactors. Karen Silkwood began working there in August 1972, performing quality control checks on those pellets in the metallography laboratory. Every day she held pellets against unexposed x-ray film, letting the gamma radiation from the pellet expose it. Even distributions meant the plutonium was evenly dispersed. Hot spots showed problems. She would also polish randomly selected pellets from each lot and check them for cracks.

In November 1972, she took part in a strike called by the local chapter of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union (OCAW); they were demanding higher wages, better training, and improved health & safety measures at the facility. After a couple of months, the strike was crushed. She returned to work with a new contract, disillusioned with the company.

Meanwhile, her personal life was in flux. Silkwood had given up custody of her three children when she and her husband divorced. And in 1973, her relationship with Drew Stevens, a colleague, had ended. In September, she even tried to kill herself by overdosing on drugs.

In early 1974, Kerr-McGee speeded up production and introduced 12-hour shifts. Soon afterwards, spills and contaminations became even more frequent. Some incidents were severe.

Two glove-box operators had filled a plastic bag with plutonium-contaminated waste (a standard procedure), when they spotted smoke coming from a hole in the bag. Plugging the hole, they ran out of the room, but not before they and five other workers had inhaled 400 times the weekly limit of insoluble plutonium permitted by the AEC.

Inhaled plutonium was extremely dangerous because it would get lodged in the lungs and alpha particles emitted by it would damage delicate tissue.

Soon after the fire, two maintenance men repairing a pump were splashed by a rain of plutonium particles that settled on their hands, faces, hair, and clothes. The plumbers left at noon to eat in Crescent, unaware of their contamination until they returned to the plant.

Worried about health & safety, Silkwood began taking greater interest in OCAW activities.

“In the laboratory, we’ve got eighteen and nineteen year-old boys…And they didn’t have schooling, so they don’t understand what radiation is.”

—Karen Silkwood

She also had trouble falling asleep, especially on days when she worked the night shift. So in May, her physician prescribed a sleeping pill called Quaalude. Over the next few months, Silkwood would build a tolerance to it.

Plutonium-239, OCAW, and the AEC

She was working in the Emission Spectroscopy laboratory at 4pm on 31 July 1974, pulverising plutonium pellets and running the dust through a spectrograph to check for other elements. After she had left for home, technicians checked air filters used in the lab during the previous three shifts. The filter papers used during Silkwood’s shift were found to be highly contaminated.

After testing urine & faecal samples of every worker who had been in the lab during that shift, only Silkwood’s sample came back positive for plutonium-239. But the source of contamination wasn’t found, and the level of contamination wasn’t really significant by AEC’s standard.

A week later, Silkwood was elected to a three-member union committee responsible for collective bargaining with management.

Meanwhile, one of Silkwood’s colleagues in the union wrote to OCAW’s vice-president about the precarious state of health & safety at the Cimarron facility. Instructed to quietly gather evidence, Silkwood maintained detailed observations of contamination incidents in August and September in a small spiral notebook she carried.

On 26 September, the committee travelled to OCAW’s Washington office and met Anthony Mazzocchi. When they briefed him about all the contamination incidents observed since Kerr-McGee ramped up production, Mazzocchi grew worried. When he mentioned the link between plutonium and cancer, the three Kerr-McGee employees became upset.

Nobody had told them, until then, that exposure to plutonium had been linked to cancer. What little health & safety training they had received at Kerr-McGee had completely neglected this linkage.

Towards the end of the meeting, Silkwood mentioned that contamination wasn’t the only problem at Kerr-McGee. The company, she said, was tampering with quality control.

She told Mazzocchi that fuel-rod quality-assurance records were being doctored. She wasn't sure what faulty fuel rods might do when they were used at the Westinghouse Fast Flux Test Facility, but tampering was serious.

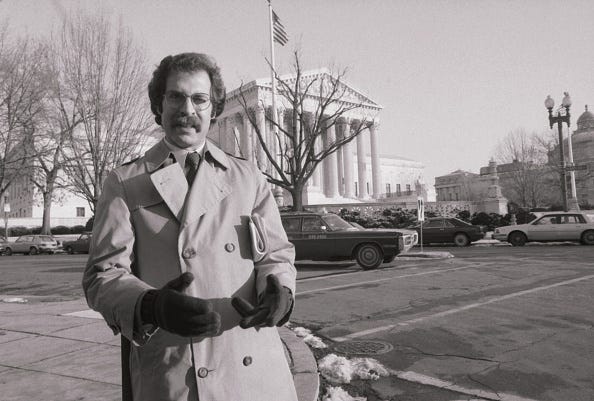

Mazzocchi warned them not to mention the quality control issue when meeting the AEC. The next morning, his assistant, Steven Wodka took the Kerr-McGee employees to Bethesda, Maryland to meet seven members of the AEC at its headquarters. Silkwood and her colleagues cited 39 incidents to buttress their case that Kerr-McGee was failing to keep exposure to plutonium as low as possible.

The AEC promised to investigate all the allegations, but the union members did not expect much. They knew the AEC was, to an extent, compromised. In its role as a regulator, the AEC often conducted surprise inspections of the Cimarron facility. Except the plant management were warned by someone within the AEC betwee 3 days to a week in advance of the visit, giving them enough time to brush things under the carpet.

After the meeting, Mazzocchi sought Silkwood’s help to nail Kerr-McGee on the quality control issue. He would leak information to the New York Times in December just before the union negotiated a new contract for workers at the Cimarron plant. But for that, he would need Karen to gather information.

“If the charges are substantiated,” he told her privately, “it would be dynamite. But there's no way we can give them to the Times without substantiated information.”

“Facts!” he told her. “No assertions. They won't fly in a newspaper.”

“I can get them,” she said.

Snooping & advocacy

The meeting in Washington gave Silkwood a sense of purpose, and she latched on fiercely

After finishing her work, she spent time in the Metallography lab studying quality control records and x-rays. And in time, she noticed that someone was touching up x-rays to hide defects. She would frequently call Wodka to report on her progress.

“We grind down too far and I've got a weld I would love for you to see, just how far they ground it down till we lost the weld, trying to get rid of the voids and inclusions and cracks.”

—Karen Silkwood

In October, when her friend Jean Jung was affected by a contamination incident, Silkwood accompanied her to health physics and urged her to insist on getting a nasal smear test to determine how much plutonium had been inhaled. This annoyed the supervisor who was trying to downplay the incident, and the two of them got into a heated argument.

Both Jean Jung and her colleague, nineteen-year-old Don Kirk, had high nasal smears: they had both inhaled significant amounts of plutonium. But nobody had told Kirk that plutonium was carcinogenic, and he was blasé about the whole thing.

“A high nasal smear? — Oh, yeah,” he told her. “I was on the a.m. shift and I worked in the room with six hot gloves during production and they didn't check them until the next day.”

Her fierce advocacy for colleagues who had suffered plutonium contamination brought her onto Kerr-McGee’s radar. But it wasn’t the only red flag.

Contamination

Sometime in October, Silkwood appeared to have stumbled upon an even more frightening discovery while tracing quality control documents for various batches of plutonium pellets. She confided in James Noel, a friend and colleague, that more than 40 pounds of plutonium was missing from the Cimarron facility. This was enough to make 3-4 nuclear weapons. And the worst part was, nobody was even looking for it. Noel made a note of their telephone conversation in his desk log.

The strain of all that she had found out must have affected her severely, because in October her friend Evelyn Emerich noticed that Silkwood looked pale and spoke with slurred speech. When she asked what was wrong, Silkwood told her that the medication her doctor had given her to help her sleep made her feel sick.

Towards the end of the month, Silkwood rang her sister and, crying, claimed that someone was trying to do something to her. The next time she called her, Silkwood said she was planning to quit in December.

All the while, Silkwood continued gathering data. And despite her best efforts, she wasn’t very subtle about it. Kerr-McGee denied knowing anything about her snooping, but her colleagues had certainly noticed her behaviour. Gary Longaker, a lab analyst, later testified:

“It was sort of a running joke there about watching Karen…she would come into a room where you were working, and she would write something down on a notebook, and then leave.”

Tuesday

On 5 November, Silkwood was formally reprimanded for taking prescription drugs without informing Kerr-McGee. She then went to work in the Metallography lab, labelling and grinding plutonium pellets. At 6:30pm, she checked her hands and lower arms for contamination on a wall-mounted monitor. It began emitting a clicking sound. A health physics technician came and monitored her with more sophisticated equipment.

The right sleeve and shoulder of her coveralls were contaminated forty times more than the level deemed safe by the AEC. Contamination is measured in disintegrations per minute (d/m). The AEC safe limit is 500 d/m; Silkwood, in her clothes, read 20,000 d/m.

Next, they had her proceed to a decontamination hall. There, she stripped so that her skin could be checked thoroughly.

Karen's left hand, right wrist and upper arm, neck, face, and hair. The highest level was on the right wrist — 10,000 d/m, or twenty times over the limit declared safe by the AEC.

Nasal smears were also positive, suggesting that she had inhaled considerable quantities of plutonium dust that day.

After decontamination — showering and washing her skin with a mix of Clorox and Tide — no part of her skin measured more than 500 d/m. She returned to the lab, finished doing paperwork, and went home 12 hours after she had reported to work.

Wednesday

The next morning, about an hour after she began work at the office doing paperwork, the monitor needle jumped again just as she was getting ready to attend contract negotiations on behalf of the union. After washing her right forearm with soap, she took part in negotiations all day. Upon returning to the lab late in the afternoon, the monitor showed that her forearm, neck, and face were contaminated, reading 5,000 d/m. Nobody had any explanation about where the contamination might have happened, because she hadn’t set foot inside any part of the facility with radioactive materials that day.

After thorough decontamination — scrubbing her skin until it was pink and raw — health physics technicians took a nasal smear. Even though she hadn’t handled any radioactive materials that day, the readings, at 171 d/m, were about 30 d/m higher than Tuesday’s reading. Silkwood was now convinced, despite soothing opinions to the contrary expressed by technicians and higher ups in health physics, that the contamination picked up by the monitors was plutonium already inside her lungs that she was breathing out. And her already strained mental health took a turn for the worse.

Thursday

Silkwood’s nasal smears measured an incredible 45,000 d/m shortly after reporting to work in the morning. The faecal sample she had brought in that morning measured between 30,000 and 40,000 d/m. A quick check of her locker and car showed negligible contamination.

Kerr-McGee health physics technicians then accompanied her to her apartment. There, they found significant contamination in the kitchen (400,000 d/m on a package of bologna and cheese in the refrigerator) and bathroom (100,000 d/m on the toilet seat, 40,000 d/m on the floor mat, 20,000 d/m on the floor). The levels in the rest of the house weren’t significant, and no plutonium was found outside. Her roommate wasn’t contaminated.

Strangely, Silkwood’s urine samples collected at home showed very high radiation levels, but those collected at Kerr-McGee did not, leading a few at Kerr-McGee to suspect that Silkwood was smuggling plutonium out of the facility. When questioned about the people who could have had access to the house, Silkwood confessed that she left her house unlocked because her roommate — who worked the graveyard shift — often had trouble with the lock. Anyone could have contaminated her house, she insisted.

Los Alamos and Highway 74

To try and resolve the mystery conclusively, Kerr-McGee sent Silkwood, her boyfriend, and her roommate to the Los Alamos National Laboratory for further investigations on Sunday. While the latter two did not have significant plutonium in them, the physician informed Silkwood that her lungs were estimated to have 6-7 nanocuries of plutonium in them. He neglected to inform her, however, that the estimate was on the lower end of a range which extended beyond the safe threshold set by the AEC.

Silkwood and her companions returned to Oklahoma late on 12 November. The next day, in the evening, Silkwood attended a union meeting at a place called the Hub Cafe. Her friend — Jean Jung — noticed her leafing through documents in a thick envelope she was carrying. There even appeared to be a few photographs in there.

At 6pm, she called her boyfriend and asked him to pick up Wodka and the NY Times reporter accompanying him from the airport. She had collected everything she needed, and would meet them in a couple of hours at the Northwest Holiday Inn in Oklahoma City, she told him.

Silkwood took Jung aside after the meeting had ended.

“She then said there was one thing she was glad about,” Jung swore in her affidavit. “That she had all the proof concerning falsification of records. As she said this, she clenched her hand more firmly on the folder and notebook she was holding. She told me she was on her way to meet Steve Wodka and a New York Times reporter ... to give them this material.”

After that, Silkwood left for Oklahoma City. Less than thirty minutes later, she was dead.

When the police investigated her car after the accident, they did not find the documents or her notebook.

Continued in Part Two.

Have you read my spy novels? The Let Bhutto Eat Grass series sees a motley crew of spies try to halt nuclear weapons espionage during the Cold War.